Shifting Power Dynamics in the Asia-Pacific: How Small and Medium Powers are Adapting to the New International Order

Journal: Journal of Globalization Studies. Volume 15, Number 2 / November 2024

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/jogs/2024.02.05

Saman Bayat, Imam Khomeini International University, Qazvin, Iran

The Asia-Pacific region is currently undergoing a significant shift in power dynamics as the international order transitions fr om a period dominated by the United States to a more competitive global environment. This transition has created opportunities for small and medium-sized powers in the region to strengthen their influence and improve their strategic position both regionally and internationally. This article aims to examine how these powers are adapting to the new international order and explores the consequences of their approaches. The article argues that given the limited effectiveness of interdependence in creating deterrence during recent international crises, small and medium powers must adopt new strategies to achieve their goals and enhance their position in the face of increasing competition between revisionist and conservative powers. The article emphasizes the growing importance of establishing reciprocal interdependence in the geo-economic and geo-political dimensions in shaping the strategies of small and medium powers in the Asia-Pacific region. This approach is considered necessary for smaller nations to achieve their goals in the new international order.

Keywords: Asia-Pacific, shifting power dynamics, small power, medium powers, competitive global environment.

1. Introduction

The international system is a dynamic entity, constantly evolving in response to a myriad of factors. Throughout history, transformative shifts have reshaped the global landscape, giving rise to new powers and structures that challenge the established order. Environmental pressures and disruptive events can further unsettle the delicate balance of the international system, prompting adaptations and realignments. This cyclical nature of the international system is evident in the four distinct phases: emergence, escalation, stabilization, and decline.

The end of the Cold War marked a pivotal moment in international relations, ushering in an era of unprecedented fluidity. The global stage is now characterized by a complex interplay of events, challenges, and uncertainties, requiring a more holistic and inclusive approach to governance. The rise of centripetal forces has fostered a multipolar world, with multiple centers of power vying for influence and shaping the dynamics of the international system.

Emerging non-Western powers are increasingly asserting their presence on the global stage, changing the traditional power dynamics. Regional systems, such as the Asia-Pacific, are particularly affected by the tensions between status quo powers and those seeking to reshape the existing order. Despite its economic prowess and efforts to maintain peace and stability, the Asia-Pacific region grapples with persistent challenges, including the nuclear standoff on the Korean Peninsula and territorial disputes in the South and East China Seas. The evolving world order, heavily influenced by the actions and reactions of the United States, China, and Russia, has profound implications for developments in the Asia-Pacific.

As the international system navigates this transitional phase, this paper delves into the impact of this fluid environment on the relationships between medium and small powers in the Asia-Pacific region. The previous order was characterized by a rigid hierarchy, with great powers dictating the rules of engagement. However, as competition between revisionist and conservative powers intensifies and a new era of order transformation emerges, small and medium powers are actively seeking to enhance their position in the future order and strengthen their strategic leverage.

2. The Position of Regions and Small and Medium Powers During the Transition

Period in the International Order

The terms ‘middle powers’ and ‘regional powers’ are increasingly employed by politicians, pundits, and scholars, despite their inherent ambiguity and the ensuing controversy over their meanings. Middle powers typically denote states positioned in the middle on the international power spectrum, just below Great powers or great powers, with considerable influence and the capacity to shape global developments. Although the concept can be traced back to the writings of the sixteenth-century Italian philosopher Giovanni Botero, the formal categorization of ‘middle powers’ probably originated during the 1815 Paris Summit, where several such states participated in various capacities. Contemporary literature engages in dynamic debates regarding the definition, classification, and assessment of the actions of middle powers (Yılmaz 2017: 58). Bernard Wood identifies a specific set of middle powers, examining their roles and recognizing sources of power such as population size, military strength, prestige, and influence (Wood 1987: 5).

Another perspective views middle powers as playing a stabilizing role in the international system, motivated by self-interest. Driven by concerns about global instability and vulnerability, middle powers actively seek conflict reduction, endorsing institutionalization and adherence to international laws to maintain stability, order, and predictability in the international arena (Jordaan 2017: 4). outlined four categories of middle powers, including the ‘geographical,’ situated between major powers, the ‘normative,’ acting as an honest intermediary, the ‘situational,’ relative to larger and smaller states, and the ‘behavioral,’ engaging in specialized diplomacy to prevent or resolve crises. A ‘behavioral’ middle power may act as a catalyst, attracting followers, or as a facilitator, managing the institutionalization and organizational aspects with an emphasis on planning, organizing meetings, setting priorities, and issuing statements (Cooper, Higgott, and Nossal 1990: 24–25 and Patience 2014: 214).

A more conventional approach to defining a ‘middle power’ hinge on a state's military capabilities, economic strength, and geostrategic position. The second, and arguably more critical, approach seeks to assess a government's leadership capacity, influence, and legitimacy in the international arena. Middle powers typically endorse multilateralism and employ ‘specialized diplomacy’ to pursue specific foreign policy goals within the constraints of their comparatively limited capabilities. A regional power, on the other hand, is a government that wields influence over a specific region. If unrivaled in its region, a state can ascend to the status of a regional hegemon. Regional powers exhibit substantial military, economic, political, and ideological capabilities, allowing them to shape the security agenda of their respective regions (Yılmaz 2017: 64).

Concerning small powers, Thorhallsson and Steinsson emphasize that definitions of small powers focus primarily on the scarcity of resources and capabilities determining power and influence. Size is often determined by factors such as population, territory, economy, and military power (Thorhallsson and Steinsson 2017). However, some argue that size is a relative concept, with major powers exerting much greater influence than middle powers, whose influence, in turn, surpasses that of smaller powers (Morgenthau 1972). Small states generally lack the capacity to exert influence on the international stage (Keohane 1969). The concept of ‘smallness’ is context-dependent and varies according to factors such as population indicators, GDP, and military strength. Achieving a nuanced understanding requires differentiating between quantitative and qualitative approaches in analyzing and defining a small state.

David Vital points out that all states, regardless of size, have strengths and weaknesses. In a realist approach to small states' theory, limited influence is a common characteristic, though not universal. Small powers can be highly relevant in international relations, encompassing political and social aspects, acting as indicators of ‘foreign policy power’ (Vital 19980, Long 2017a). Thorhalsson's framework integrates multiple factors, including population size, territory, sovereignty, government recognition, military capabilities, internal cohesion, and foreign policy consensus. Economic size, perceptual size, and preference size, each of equal value, contribute to a comprehensive understanding of small states (Thorhallsson 2006: 25).

The post-war liberal international order, forged by the victorious Great powers after World War II, with the United States of America at the forefront, aimed to establish a framework based on multilateralism and institutionalized economic structures. It sought to foster open markets, international institutions, cooperative security, a democratic society, and the rule of law. The United States, in particular, played a pivotal role in shaping this order, emphasizing the promotion and preservation of liberal values.

Since the end of the Cold War, the notion of a unipolar world dominated by global trade has provided a political framework. This framework has paved the way for diverse geopolitical narratives and strategies, as different powers pursue their respective interests. The emerging powers exhibit two distinct intentions based on their behavior and foreign policy objectives: revisionist and conservative. Revisionist governments express dissatisfaction with their current standing, seeking to undermine the existing order to enhance their power and prestige. Conversely, conservative governments accept and actively work to maintain the prevailing international system (Chandra 2018 12).

As global perspectives on socio-economic development evolve, an increasing number of individuals and governments challenge the Western narrative. Countries around the world are reclaiming their identities and constructing alternative narratives rooted in diverse values, cultures, and heritage. This diversity shapes different visions of lifestyles, economies, and democracy.

The formation of a political alliance among the United States of America, the European Union, and regional allies in the Asia-Pacific region signifies a geopolitical alignment. Additionally, these entities represent three economic poles. The United States and the European Union aim to counter Russia through NATO expansion, while the United States, along with the ‘Quad’, strengthens its military alliance in response to China (Yang 2005: 295). Small revisionist powers employ strategies such as promoting anti-Western sentiments and supporting anti-Western groups to gain influence. Meanwhile, southern countries witness a cultural and social movement striving to reclaim their identity, shape alternative ideals for the future, and secure better representation in international institutions. This movement seeks to challenge existing narratives and assert a more influential role in shaping changes in the international order.

Regions have consistently played a crucial role in international relations, with two distinct waves of regionalism shaping the landscape. The initial wave unfolded fr om the 1950s to the 1970s, and the subsequent wave, often labeled as the ‘new regionalism’, emerged in the 1980s and gained recognition among scholars in international relations and political economy (Mousavi Shafaee 2015: 153). The post-Cold War era marked a pivotal moment as regional cooperation transcended military and security collaborations, expanding to encompass political, economic, social, and cultural alliances. This evolution highlighted the diminishing influence of global powers in regions aligned with international system developments. Notably, major powers shifted fr om manipulating regional issues to a more cooperative approach, refraining fr om imposing their interests on these regions (Ibid.).

The newfound autonomy of regional powers within the international system provided them with opportunities to actively contribute to shaping a world order aligned with their needs and interests. In parallel, these regional powers assumed responsibility for ensuring peace and security in their regions. Regional powers, with their capacity and regulation of procedures and regimes in the regions, are eager to convince other countries in the region to follow them in order to change the global arrangements in line with their goals and interests in the new international order. Cultural affinities and regional proximity, exemplified by the shared culture among northern European countries, served as catalysts for commercial and cultural cooperation, fostering political collaboration and establishing order in the region (Mousavi Shafaee 2015: 160).

Conversely, the regional level operates on a dual front in shaping the global structure. Governments worldwide prioritize regional security, often above global security concerns. Security dynamics are concentrated within specific regions, where positive trends may characterize one region, like Latin America, while negative trends prevail in another, such as the Middle East. Security concerns in these areas are primarily rooted in relationships among regional actors, with perspectives ranging fr om non-state actors and post-traditional security issues to a focus on states and traditional security. Post-Cold War era theories, predominantly originating in the United States, adopt a top-down perspective, creating a bias in the conceptualization of polarity. This has led to the interchangeable use of terms like ‘great power’, often applied specifically to regional powers, highlighting the need for a more comprehensive analysis of superpowers, great powers, and regional powers (Wæver 2017: 459–461).

Shiping Tang contends that the post-Cold War international order was predominantly imposed by the United States and its allies, reflecting a top-down approach. However, there is now a discernible shift in law-making and global governance reform, transitioning from a top-down to a bottom-up approach (Tang 2018: 125). This shift is underscored by the major changes in the international order, historically enforced by Great powers following victories in major wars. Today, the absence of feasible major wars among great powers results in a lack of power or influence to impose such orders. Furthermore, a significant shift in global power from the West to the East challenges the traditional center of power held by the West, potentially jeopardizing the ability to maintain global order. In this evolving landscape, non-state actors gain increasing influence in rule-making, marking a departure from the historical dominance of governments in the concentration of power since 1648.

Regionalization intensifies this shift, constraining global governance with a proliferation of regional initiatives. More rules are now crafted from the bottom-up, reflecting a departure from top-down imposition (Tang 2018: 125). In the current asymmetric multipolar world, great powers face limitations in recruiting allies from regional powers and persuading alignment with their interests. The Cold War-era competition among great powers for allies in the Global South, as well as regional powers like India, Brazil, and South Africa, has evolved. The declining power of the West, particularly the United States, reduces their capacity for recruitment. Similarly, China, despite significant investments and economic loans, struggles to maintain friendships and alliances. In this scenario, middle and small powers find themselves with increased freedom to choose and respond to the overtures of major powers (Balta 2022).

3. Interdependence in the Period of Transition in the International Order

During the late 1960s through the 1970s, the international system underwent substantial transformations, characterized by a complex web of relationships as nations pursued collaboration. Amidst the weakening of Cold War alliances due to escalating tensions, a novel focus on politicized economic issues emerged. Edward Morse, Joseph Nye, and Robert Keohane, in their work ‘Power and Interdependence’, together with Richard Cooper's articles on economic interdependence, presented a groundbreaking theory addressing international concerns. Their objective was to illustrate the susceptibility of governments and global societies to events and trends in other nations and their consequent impact on international relations.

The roots of the interdependence theory lie in internationalist ideologies, with its intellectual origins tracing back to studies of regional integration. Expanding upon regional convergence theory, interdependence theorists addressed diverse issues concerning international economic interdependence that Emerged in the 1970s. Positioned as one of the perspectives linking micro and macro analyses, the theory encompasses fundamental concepts such as interdependence, sensitivity, strength, vulnerability, costs, symmetry, and asymmetry. Within the interdependent system, power remains central, emerging as the primary factor influencing political bargaining. Power, according to Keohane and Nye, signifies the ability to control resources to achieve goals. Conversely, evaluating a country's vulnerability is a strategic policy measure employed by other nations to gauge their ability to shield themselves from the adverse impacts of global events (Keohane and Nye 2012: 231–234).

While simple interdependence is prevalent, achieving complex interdependence proves challenging, representing a mature, developed, and stable form of interdependence. Complex interdependence involves alliances characterized by mutual strategic trust, shared security frameworks, and well-established, regulated relationships. In a broad sense, dependence refers to a state heavily influenced or entirely shaped by external forces. interdependence, in simple terms, refers to a two-way dependence. In global politics, mutual dependency refers to a situation wh ere reciprocal influence exists between countries or internal actors of different countries.

Influences exerted on nations often emanate from international exchanges, involving the global transfer of money, goods, people, and messages. Since the Second World War, these exchanges have soared, witnessing a consistent ten-year doubling trend in various forms of links between individuals across borders (Smith 2000: 45). Mutual dependence measures the degree of dependence between two parties, classified as asymmetrical or symmetrical interdependence. Asymmetry implies that one party is completely dependent on the other, creating vulnerability to the exercise of power (Lilliestam and Ellenbeck 2011: 382). The more powerful party exploits this dependence, establishing asymmetrical interdependence as a powerful source of power (Proedrou 2007: 332).

Institutional and economic interdependence reduce motivations for conflict, yet they are not foolproof against war (Tønnesson 2015: 302–303). Governments may use force for geopolitical reasons, disregarding potential costs, demonstrating that competition can undermine economic interdependence (White 2012: 45–50). Huawei Zheng introduces the concept of fragile interdependence, opposing the notion of complex interdependence. In the current era of evolving international systems and superpower competition, fragile interdependence posits that interdependence is unstable, reversible, and prone to change (Zheng 2020: 10–20).

Zheng contends that in fragile interdependence, two parties rely on each other for functional needs, but do not consider each other reliable military allies or true friends. This makes their interrelationship unstable, reversible, and susceptible to change. Deeper needs dictate that an actor cannot safely depend on an unreliable other, leading to the termination or reversal of reciprocity when parties do not perceive each other as friends or reliable allies (Zheng 2020: 10–20). This vulnerability during geopolitical disorder exposes the economic layer, even at the cost of incurring losses.

In a detailed examination of the relations between Russia and the European Union, the author posits that the dynamics of their trade interactions have been significantly impacted by geopolitical shifts stemming from the Ukraine crisis and the triangular power competition involving China, Russia, and the USA in the global arena. The degree of interdependence between Russia and the EU is demonstrated to be inflexible, marked by a swift distancing and active pursuit of alternative relationships. This evolution, from strategic partnership to increased competition and ultimately escalating into direct conflict, underscores the non-permanent nature of interdependence; states can indeed reduce their interdependence with each other.

In contrast, the historical records reveal numerous conflicts between major powers, with the First and Second World Wars epitomizing the peak of such confrontations. After the Second World War, the conflicts between countries in the southern hemisphere escalated, which prompted northern countries to redirect their disputes towards the South in order to avoid direct confrontation. During the Cold War, southern regions became arenas for superpower competition, with the policies of Great powers influencing conflicts (Ayoob 1995). In the contemporary era, the expansion of the regional system has caused great powers competition to shift to the regional level, impacting medium and small powers. Events such as the conflict in Ukraine, competition between the US and Russia, tensions between China and the US in the South China Sea and Taiwan, conflicts in Nagorno-Karabakh, and the Syrian civil war illustrate this shift. As a result, the influence of these conflicts on the affected regions is heightened by the bottom-up dynamic of small powers and regions depending on great powers, along with asymmetric interdependence.

There are different perspectives on the role of economic interdependence in either promoting or undermining international peace. Some argue that increased economic interdependence fosters peace by generating economic gains from trade, influencing political conflicts, and pressuring governments to search for peaceful solutions. This perspective envisions a scenario in which economic prosperity incentivizes the maintenance of peaceful diplomatic interactions, prioritizing them over previous security concerns. However, this view primarily applies to the post-Cold War unipolar system in which the United States stands as the sole managing power.

The shift from a unipolar to a multipolar system brings about complexities. Economic interdependence may not always indicate international peace. Its impact depends on specific conditions and can even strain relations between countries. The interaction between powers that uphold the current state of affairs and those that strive for change significantly affects economies, potentially leading to tensions and ripple effects on areas of cooperation. As the global order changes, medium and small powers aim to not only adapt but also to increase their influence, necessitating foreign policy consensus to effectively navigate the evolving global system.

4. Asia-Pacific in the Period of Transition in the International Order

According to Gilpin, one of the unique features of the contemporary era shaping the new world order is its starting point. Historically, new international systems are formed at the end of a great war or a hegemonic war. These destructive wars destroy the old order and form the victorious powers of the new order (Gilpin 2016: 15–20). However, today, this situation no longer exists. In today's world, wh ere economic and technological interdependence has intensified, it is no longer possible to talk about the traditional distribution of economic and military power.

Many actors are seeking to enhance their interests and strategic position in the new international order. This is especially true for small and medium powers that want more participation. They believe that the distribution of power and their global role in international politics is unbalanced. On the other hand, the changing international order has led to increased tension between globalization and regionalization, as well as competition between revisionist powers and the existing situation in various regions. One such region is the Asia-Pacific region, which, due to its geopolitical and geoeconomic importance, has become a focal point for great power competition in recent years. As a result, medium and small regional powers will also play a greater role in shaping the laws and institutions governing international economic and political affairs.

A clear example of the increasing importance and role of small and medium actors is the redefinition of the Asia-Pacific as the Indo-Pacific. This shift denotes the convergence of the Indian and Pacific Oceans in Southeast Asia, reflecting pragmatic politics and significant geopolitical changes during the global transition of the international order. Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's 2007 proposal for a 'Crescent of Freedom and Prosperity in Greater Asia' exemplifies this trend. Understanding each country's geographic definition of the Indo-Pacific is crucial for effective policy-making, collaboration, and trust-building, as misunderstandings can lead to false expectations and potential mistrust (Gilpin, 2016).

No nation modifies the definition of a fundamental concept without valid justification. Therefore, changes in the geographical delineation of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ should be interpreted as indicative of policy shifts (Haruko 2020: 3). Japan, as the originator of this concept, has embraced and refined its approach, branding it the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy’. Tokyo's expanded geographic scope now encompasses the western Pacific Ocean, Southeast Asia, with ASEAN serving as the nexus between the two oceans, and the most of the Indian Ocean, including South Asia, the Middle East, and the coastal countries of East Africa. Notably, Japan skillfully involves China in this constructed framework, steering clear of alignment with China's containment strategy. In 2017, the United States announced the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy’ as its regional strategy. This strategy aligns with Japan's approach, but with a military-strategic focus. It aims to restrain and create a balance with China and emphasizes close cooperation with QUAD members (America, India, Australia, and Japan) as well as some smaller countries like South Korea, Vietnam, and Indonesia (Poonkham 2022: 2).

China openly opposes the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept, interpreting it as a US-led containment strategy to counter its expanding economic and military prowess. China chooses not to be included in the Indo-Pacific, favoring the prestige of the Asia-Pacific region. China's presence in the Indian Ocean through the Belt and Road Initiative underscores its economic and military influence. Russia perceives the US presence in North and Northeast Asia as illegal and a threat to its national security. Moscow views the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept as an attempt to restrain both China and Russia, aligning itself with Beijing to counter the growing influence of the Indo-Pacific concept (Haruko 2020: 4). In studies of interstate conflict, scholars argue that states consider various factors, including interdependence levels, predictions of third-party behavior, and the likelihood of success in a multi-sided confrontation before initiating conflict (Aydin 2010: 524). Uncertainty regarding the conflict's outcome and the predictability of intervention serve as strong deterrents.

In a case study, the researchers examined the Ukraine crisis and EU-Russia relations. By measuring the degree of interdependence, they argue that the degree of economic interdependence between Russia and EU member states does not seem to have a significant impact on the support for sanctions. Additionally, the presence of members from different countries among the members of the European Parliament challenges the logic of economic interdependence that underlies the liberal principle. This principle suggests that interdependent states should generally avoid conflict due to their economic interests relative to less interdependent states (Silva and Selden 2019: 246–248).

Therefore, considering the competition between the United States of America and China, as well as the alliances and coalitions formed in the Asia-Pacific region, some believe that due to the interdependence and multilateralism created at the regional and global levels, there is no possibility of conflict. However, it can be argued that the situation between Russia and the European Union, caused by the competition between the United States of America and Russia in the European region due to the Ukraine crisis, can be generalized to the Asia-Pacific region. Although a conflict like the one in Ukraine has not yet occurred, there are many similarities and commonalities. These include the presence of competition and containment policies between two Great powers (America and China), the existence of a region (Asia-Pacific), and the involvement of a third country (Taiwan) as a means of containment in the conflict between the two superpowers. The most important thing is the interdependence that exists. In this study, we examine the degree of interdependence between the Asia-Pacific region (consisting of the 13 largest countries in the world economy) and the United States of America and China. We utilize Oneal's interdependence formula (Oneal 1996) to measure this interdependence. The formula calculates the amount of bilateral trade as a share of GDP.

Table 1

Asia-pacific member-state economic interdependence with the USA

A-P to USA | EX-m$ | IM-m$ | GDP-m$ | interdependency |

China | 577,636.30 | 180,839.99 | 17,730,000 | 0.042779261 |

Australia | 12,226.74 | 27,157.50 | 1,553,000 | 0.025360103 |

Japan | 135,774.60 | 82,663.92 | 4,941,000 | 0.044209375 |

South Korea | 96,306.81 | 73.662.47 | 1,811,000 | 0.093853827 |

India | 71,444.32 | 41,388.09 | 3,176,000 | 0.035526577 |

Indonesia | 25,820.25 | 10,104.35 | 1,186,000 | 0.030290556 |

Malaysia | 34,347.83 | 18,204.97 | 373,000 | 0.140892225 |

New Zealand | 4,194.03 | 3,820.25 | 249,900 | 0.032069948 |

Philippines | 11,859.26 | 8,277.99 | 394,100 | 0.051096803 |

Singapore | 39,316.82 | 40,573.14 | 397,000 | 0.201234156 |

Thailand | 41,079.63 | 14,379.32 | 505,900 | 0.109624333 |

Taiwan | 54,800.56 | 28,900.42 | 828,600 | 0.101014941 |

total | 1,104,807.15 | 456,309.94 | 33,145,500.00 | 0.047098915 |

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2013) ‘External Trade’ http://data.imf.org/regular. aspx?key=61013712, accessed 5 Feb 2023.

Table 1

The USA's economic interdependence with the Asia-pacific member-state

USA to A-P | EX-m$ | IM-m$ | USA -GDP-m$ | interdependency |

CHINA | 151,442.12 | 504,935.38 | 23,320,000 | 0.028146548 |

Australia | 3,935.28 | 12,466.49 | 23,320,000 | 0.000703335 |

Japan | 74,564.69 | 134,860.34 | 23,320,000 | 0.00898049 |

South Korea | 65,942.40 | 94,918.63 | 23,320,000 | 0.004367969 |

India | 40,052.17 | 73,172.59 | 23,320,000 | 0.004855264 |

Indonesia | 9,389.88 | 27,059.06 | 23,320,000 | 0.001562991 |

Malaysia | 15,174.24 | 56,117.07 | 23,320,000 | 0.003057089 |

New Zealand | 3,724.04 | 9,948.87 | 23,320,000 | 0.000586317 |

Philippines | 9,290.21 | 14,006.14 | 23,320,000 | 0.000998986 |

Singapore | 35,285.47 | 29,505.33 | 23,320,000 | 0.002778336 |

Thailand | 12,652.44 | 47,350.59 | 23,320,000 | 0.002573029 |

Taiwan | 36,837.94 | 77,064.08 | 23,320,000 | 0.004884306 |

Total | 392,348.48 | 1,081,404.57 | 23,320,000 | 0.063196958 |

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2013) ‘External Trade’ http://data.imf.org/regular. aspx?key=61013712, accessed 5 Feb 2023.

In order to determine the degree of interdependence, we have chosen the 13 most important countries in the global economy as representatives of the Asia-Pacific region. Table 1 shows that among the members of this region, Singapore is the most dependent on the United States of America with 20 per cent, while Australia is the least dependent with only 2.5 percent. The United States of America also has a degree of dependence on the Asia-Pacific countries listed in Table number 2. The highest percentage of dependence is related to China (2 %), while the lowest degree of dependence is with New Zealand.

Table 2

Asia-pacific member-state economic interdependence with China

A-P to China | EX-m$ | IM-m$ | GDP-m$ | interdependency |

Australia | 129,772.85 | 72,480.87 | 1,553,000 | 0.130234 |

Japan | 163,598.87 | 185,245.69 | 4,941,000 | 0.070602 |

South Korea | 162,912.97 | 138,628.13 | 1,811,000 | 0.166505 |

India | 23,044.28 | 87,481.74 | 3,176,000 | 0.0348 |

Indonesia | 53,781.90 | 49,926.94 | 1,186,000 | 0.087444 |

Malaysia | 46,307.11 | 55,517.36 | 373,000 | 0.272988 |

New Zealand | 12,545.41 | 10,587.12 | 249,900 | 0.092567 |

Philippines | 11,530.84 | 28,210.34 | 394,100 | 0.10084 |

Singapore | 67,746.76 | 64,610.68 | 397,000 | 0.333394 |

Thailand | 36,583.68 | 66,374.63 | 505,900 | 0.203515 |

Taiwan | 104,000.25 | 60,800.38 | 774,730 | 0.21272 |

total | 811,824.92 | 819,863.88 | 15,361,630 | 0.106218 |

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2013) ‘External Trade’ http://data.imf.org/regular. aspx?key=61013712, accessed 5 Feb 2023.

Table 3

The China’s economic interdependence with the Asia-pacific member-state

China to A-P | EX-m$ | IM-m% | GDP-m$ | interdependency |

Australia | 66,481.13 | 162,182.73 | 17,730,000 | 0.012897 |

Japan | 165,902.06 | 206,153.13 | 17,730,000 | 0.020985 |

South Korea | 150,553.94 | 213,554.72 | 17,730,000 | 0.020536 |

India | 97,588.36 | 28,028.09 | 17,730,000 | 0.007085 |

Indonesia | 60,708.88 | 63,632.76 | 17,730,000 | 0.007013 |

Malaysia | 78,918.31 | 98,159.54 | 17,730,000 | 0.009987 |

New Zealand | 8,568.62 | 16,140.50 | 17,730,000 | 0.001394 |

Philippines | 57,216.45 | 24,734.55 | 17,730,000 | 0.004622 |

Singapore | 55,039.58 | 38,702.67 | 17,730,000 | 0.005287 |

Thailand | 69,385.73 | 61,703.28 | 17,730,000 | 0.007394 |

Taiwan | 78,384.31 | 251,460.50 | 17,730,000 | 0.018604 |

Total | 888,747.37 | 1,164,452.47 | 17,730,000 | 0.115804 |

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2013) ‘External Trade’ http://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61013712, accessed 5 Feb 2023.

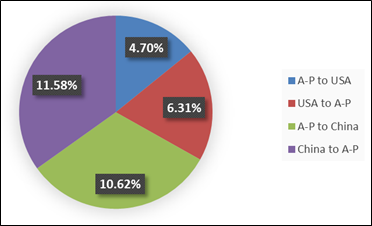

Table 3 shows the degree of dependence of Asia-Pacific countries on China. Singapore has the highest dependence rate at 33.33 per cent, while India has the lowest dependence rate at 3.48 per cent. In Table 4, China has the highest dependence on Japan and South Korea at 2 per cent, and the lowest dependence on New Zealand at 0.13 per cent. However, in an overview, we can see the mutual situation of China and America in the Asia-Pacific region in Figure 1. It shows that America is more dependent on the region at 6.31 per cent, while China is at 11.58 per cent. In contrast, the Asia-Pacific region, with a 4.70-percent dependence on America and a 10.62-percent dependence on China, shows that the region is more reliant on China than on America.

Fig. 1. China-US-Asia–Pacific Interdependence

In addition to the interdependence of the Asia-Pacific region, this region is also rich in natural resources It holds 35 per cent of the world's natural gas, 67 per cent of the world's oil reserves, 40 per cent of the world's gold reserves, 60 per cent of the world's uranium reserves, and 80 per cent of the world's diamond reserves. According to Ahmed (2021), the strategic importance of this region can be measured by several factors. First, it is home to seven of the world's ten largest armies. It is also home to six nuclear powers. Furthermore, this region contributes to two-thirds of the global GDP growth and accounts for 60 per cent of the global GDP. These statistics underline the inherent power of this region. It is fundamental. This area is also of great importance to China, as it serves as the primary route for oil supply, with 85 per cent of China's imported oil passing through the Strait of Malacca (Siddiqui Farhan 2022).

The developments that emerged in Europe in 2022 have had a destructive effect on the international system and global order. In Asia-Oceania, however, due to its geographical remoteness, these developments have only manifested as small waves in the region. The processes set in motion by the current military-political conflict in Europe and the confrontation between the West and Russia have not yet had a significant impact on Asia and the Pacific, nor have they led to the collapse of the regional order. The situation in Ukraine and the competition between the US and Russia in Europe can serve as a warning for the Asia–Pacific Just like the problems in Ukraine, we cannot ignore the issue of Taiwan. Taiwan is not just an internal matter of China, and it is no longer exclusively an issue between the US and China. The Taiwan issue is rapidly becoming an international one.

5. Response to the Transitional Situation in the International Order

The structure of the international system is currently in a state that is neither reminiscent of the previous order nor indicative of the new one. Rather, it is in the midst of a transitional process, a status aptly described as ‘purgatory’. In this phase, the use of foreign policy as a tool for great powers becomes a challenge, as the primary focus shifts to fostering the growth of small and medium-sized economies. The pivotal factor determining a country's significance in the emerging global landscape is its ability to engage in development-oriented partnerships and overcome the challenges of the past. The erosion of trust in international institutions contributes to a rapid decline, as governments and companies lose faith in the established laws designed to uphold the liberal world order.

The global economic infrastructure is now in a dynamic state, wh ere the significance of small and medium powers is increasingly prominent. Their future is no longer solely reliant on the US-led liberal world order and the benefits of globalization. In the past, these entities could mask their issues with superficial reforms and confidence, but that is no longer the case. External pressures on smaller nations are growing, and Great powers are engaging in strategic maneuvering and resource acquisition that favor their competition. Nuclear powers, in an effort to avoid direct confrontation, are likely to involve medium and small powers in proxy conflicts with each other (Bordachev 2022).

This scenario implies that medium and small powers can prevail during periods of significant change and advancements in the international system. Moreover, they have considerable freedom of choice in this situation. In the international arena, medium and small powers endeavor to enhance their decision-making capabilities and gain a future advantage through three primary strategies: leveraging inherent power, utilizing derived power, and harnessing collective power. Inherent power is linked to the material resources of an international actor and includes geostrategic elements such as geographical locations, strategic straits, and waterways, as well as energy corridors, and geoeconomic resources like oil, gas, hydrocarbons, and minerals (Bordachev 2022).

In the realm of power dynamics, small and medium-sized powers that lack substantial material capabilities can wield influence through inherent power by persuading larger and emerging rival powers to align their actions with the former's interests. The advantage of derivative power lies in the potential to enhance a state's influence through the endorsement by a great power while concurrently relinquishing some control over outcomes. Derivative power offers state the opportunity to exert significantly more influence than a third party, possibly at a lower cost. The basis for increasing collective power is the relationship between states and non-major powers. Small and medium-sized states can pursue a variety of powers, utilizing specific institutionalism, forming single-issue groupings, or forging alliances with governments to gain minimal influence (Long 2017b).

Governments must grapple with the rise of revisionist powers and prepare for an uncertain future. One approach is introspection, as demonstrated by Turkey, Iran, and India, all of which have emphasized self-reliance in recent years. Turkey and Iran have adopted the ‘dual rotation’ model, while India, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has embraced ‘atmanirbharata’, or self-reliance, aiming for economic independence and enhanced military security. Another response is to establish ad hoc coalitions, as exemplified by recent multilateral arrangements such as BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the I2U2 group (Balta 2022). However, while these coalitions serve specific purposes, they lack the rigid structure of Cold War alliances.

In the midst of these challenges, many middle and smaller powers find themselves navigating a delicate balance with larger powers. Examples include the Association of Southeast Asian Nations' response to escalating tensions between the United States and China, and Israel's deepening relations with Sunni governments in the Persian Gulf through the Ibrahim Agreement. In the Middle East, Turkey, a NATO member, maintains significant diplomatic, strategic, and economic ties with Russia. Nevertheless, Turkey has struck a delicate balance by supporting Ukraine without opposing Russia, acting as a mediator without joining the embargo regime. Turkey has emerged as a significant player in ensuring food security and establishing itself as an energy hub for Europe after the Russian invasion, leveraging its strategic position in the asymmetric multipolar world to navigate between established and emerging powers (Balta 2022).

In the contemporary global scenario, numerous nations exploit the waning influence of the international political power center to advance their narrow self-interests. Currently, such maneuvers can be viewed as a constructive form of conflict, objectively challenging a system rooted in profound injustice. Over time, the United States and Europe are anticipated to further decline, becoming increasingly Isolated, while neither Russia nor China is ready to assume their mantle. Consequently, within this geopolitical landscape, countries have the opportunity to devise new strategies to leverage existing openings. In the realm of political and economic geography, those with robust plans may gain a strategic advantage.

The post-Cold War international order rests on three pivotal pillars: the distribution of power, the institutional frameworks, and the integration of norms. However, the dynamics of power in the Asia-Pacific during the transition of the international order present a distinctive scenario. Currently, the power structure in the Asia-Pacific region is unipolar, despite China's substantial economic and military growth. Furthermore, the institutional framework in the region has been shaped by the US hegemony, even though regionalism and multilateralism have burgeoned in the post-Cold War economic and security spheres. The third pillar of normative order is characterized by prevalent norms like sovereignty, non-intervention, free trade, economic liberalization, with human rights and democracy gaining increasing influence. Kai He and Huiyun Feng (2022) assert that the balance between these three pillars will change as superpower competition intensifies in the Asia-Pacific region, particularly involving China, the USA, and Russia.

The trend towards strategic autonomy among Asia-Pacific nations is intensifying due to the surge of globalization and the declining control over the global international system. Factors influencing this shift include the COVID-19 pandemic and concerns about energy and food security following the Ukraine crisis. As a result, Asia-Pacific countries are not only striving to maintain foreign policy autonomy and avoid commitments to specific blocs or military-political groups, but are also formulating policies to advance their interests in shaping the future order during this transitional period. This entails asserting their distinctive roles, fostering widespread nationalism in crisis response, and safeguarding their sovereignty through emergency economic management and exploring avenues for international cooperation.

6. Conclusion

In the contemporary realm of political science and international relations, a significant consensus highlights the transformative shifts occurring in the post-Cold War global order, originally led by the United States. These changes are evident in the rise of new superpowers, notably China and Russia, and their inclination towards revisionist policies in the existing international system. This marks a departure from the previous unipolar dominance of the United States and its allies. However, despite this shift, the global infrastructure sustaining the previous order persists, albeit with the consequences stemming from its misuse.

The mechanism designed to penalize global power aspirants has experienced accelerated wear and tear, hindering its adaptability to contemporary developments. Mere managerial changes, as seen in previous centuries, prove insufficient to address the complexities of the present global landscape.

Central to the previous global order was the promotion of multilateralism, regionalism, and interdependence, championed by advocates of liberal democracy. This approach, rooted in the belief that interdependence fosters deterrence and mitigates conflict, is now deemed untenable in the current flux. The exhaustion of hegemonic power and its involvement in various regions to counter emerging revisionist powers renders the interdependence mechanism counterproductive. Rather than serving its intended purpose, it transforms into a double-edged sword with destructive consequences for states. This is exemplified by the dynamics between the United States, Russia, and Europe in the Eastern European region, wh ere sanctions and mutual dependence failed to dissuade Russia's military pursuits, resulting in an energy crisis and global food security challenges.

The post-World War II multilateral system, conceived to enhance international cooperation, is strained and potentially obsolete in a multipolar world. Its inadequacy is evident in responses to crises such as the one in Ukraine, as well as energy and food crises. As global power diffuses, it becomes increasingly challenging to achieve consensus in international institutions like the United Nations. This threatens the universal application of international law and human rights, which are challenged by divergent local and regional interpretations. A weakened or collapsed institutional framework jeopardizes effective responses to critical global issues, including climate change, poverty, and technological governance. The rise of nationalism, protectionism, and populism in some quarters reflects the uncertainties associated with multipolarity and its implications for multilateralism, potentially leading to a new era dominated by nationalism, protectionism, and bilateral relations.

The Asia-Pacific region emerges as a focal point for competition between the United States and revisionist powers, namely China and Russia. Beyond its geopolitical and geo-economic importance, this region is characterized by alliances, coalitions, and superpower competition, which provide opportunities for emerging powers. Small and medium-sized governments in this region, irrespective of their satisfaction with the prevailing system, share a common objective: to enhance their position in the future order. Consequently, these governments are strategically seeking to increase their influence and become integral parts of the evolving international order.

In a milieu wh ere the old order persists alongside the nascent one, medium and small actors in the Asia-Pacific region are adopting an autonomy strategy. This strategy, based on inherent power, derived power, and collective power, aims to establish reciprocal geostrategic and geo-economic interdependence, minimizing reliance on hegemonic power. The aim is to reduce dependence on hegemonic power as the Asia-Pacific region asserts itself and recalibrates power dynamics, a trend emphasized by China's declining population ratio.

The new international order witnesses the rise of new actors seeking independence from American influence in their respective regions. The restoration of Russian power by Putin, China's multifaceted growth and economic influence, and the European Union's efforts to enhance its global standing contribute to reshaping of the future international order. Technological advances in Japan, economic growth in India and Brazil, and collaborative efforts towards a multipolar system further contribute to this transformation, making the rules-based international order less and less Western-centric.

Governments' behavioral patterns are no longer fixed on traditional blocs and alliances, as seen during the Cold War era. The future international order will be more bottom-up, regionalized, and fragmented. Inter-regional coordination and cooperation become critical, and regional actors that were once in the US sphere now establish relationships with China, Russia, and other powers seeking to revise the existing order. These governments adopt a cooperative approach while competing and a competitive approach while cooperating, emphasizing strategic autonomy. They prioritize their relative advantages and play an independent and proactive role in securing national interests and influencing others. However, they also engage with the Great powers of the new order without adhering to a specific structure, imposing their desired order on the surrounding world. Many important developments and geopolitics in the future world order will depend on the behavior of these governments.

These governments pursue global Agendas independently of Washington and Beijing, and have the determination and capacity to implement them. They use their economic advantages to bolster their position and influence, becoming more demanding, flexible, dynamic, and strategic than in the twentieth century. Whatever their common interests with the great powers, they often opt for multiple alignments, making them crucial and sometimes unpredictable Actors in the coming phase of globalization and the next phase of great power rivalry. Their importance will lead to new forms of international cooperation.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Z. 2021. Great Power Rivalry in Indo-Pacific: Implications for Pakistan. Strategic Studies 41 (4): 56–75.

Aydin, A. 2010. The Deterrent Effects of Economic Integration. Journal of Peace Research 47 (5): 523–533.

Ayoob, M. 1995. The Third World Security Predicament: State Making, Regional Conflict, and the International System. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Balta, E. 2022. A Constitutive Moment. Institut Montaigne. URL: https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/analysis/constitutive-moment.

Bordachev, T. 2022. Factors Influencing the World Order's Structure. Institut Montaigne. URL: https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/analysis/factors-influencing-world-orders-structure.

Chandra, V. 2018. Rising Powers and the Future International Order. World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues 22 (1): 10–23.

Jordaan, E. 2017. The Emerging Middle Power Concept: Time to Say Goodbye? South African Journal of International Affairs 24 (3): 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2017.1394218.

Gilpin, R. 2016. From APEC to Xanadu. Routledge.

Haruko, W. 2020. The ‘Indo-Pacific’ Concept: Geographical Adjustments and Their Implications. RSIS Working Paper, No. 326. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University.

He, K., and Feng, H. 2022. International Order Transition and US-China Strategic Competition in the Indo-Pacific. The Pacific Review 35 (1): 1–20.

Higgott, R. A., and Cooper, A. F. 1990. Middle Power Leadership and Coalition Building: Australia, the Cairns Group, and the Uruguay Round of Trade Negotiations. International Organization 44(4): 589–632. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818300035414.

IMF – International Monetary Fund. 2013. External Trade. URL: http://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61013712. Accessed February 5, 2023.

Keohane, R. 1969. Lilliputians' Dilemmas: Small States in International Politics. International Organization 23 (2): 291–310.

Keohane, R., and Nye, J. 2012. Power and Interdependence. Boston, MA: Longman.

Lilliestam, J., and Ellenbeck, S. 2011. Energy Security and Renewable Electricity Trade – Will Desertec Make Europe Vulnerable to the ‘Energy Weapon’? Energy Policy 39 (6): 3380–3391.

Long, T. 2017a. Small States, Great Power? Gaining Influence through Intrinsic, Derivative, and Collective Power. International Studies Review 19 (2): 185–205.

Long, T. 2017b. It′s not the Size, It′s The Relationship: From ‘Small States’ to Asymmetry. International Politics 54: 144–160.

Morgenthau, H. 1972. Science: Servant or Master? New York: New American Library; Distributed by Norton.

Mousavi Shafaee, S. M., and Naghdi, F. 2015. Regional Powers and World Order in the Post-Cold War Era. Geopolitics Quarterly 11 (40): 148–176.

Oneal, J., Oneal, F., Maoz, Z., and Russett, B. 1996. The Liberal Peace: Interdependence, Democracy, and International Conflict. Journal of Peace Research 33 (1): 11–28.

Poonkham, J. 2022. The Indo-Pacific: A Global Region of Geopolitical Struggle. International Studies Center (ISC). URL: https://isc.mfa.go.th/en/content/the-indo-pacific-a-global-region.

Proedrou, F. 2007. The EU-Russia Energy Approach under the Prism of Interdependence. European Security 61 (3–4): 329–355.

Patience, A. 2014. Imagining Middle Powers. Australian Journal of International Affairs 68 (2): 210–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2013.840557.

Siddiqui Farhan, H. 2022. US Indo-Pacific Strategy and Pakistan's Foreign Policy: The Hedging Option. Strategic Studies 42 (1).

Silva, P. M., and Selden, Z. 2019. Economic Interdependence and Economic Sanctions: A Case Study of European Union Sanctions on Russia. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32 (3): 374–394.

Tang, Sh. 2018. The Future of International Order(s). SSRN, May 15. URL: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3179295.

Thorhallsson, B. 2006. The Size of States in the European Union: Theoretical and Conceptual Perspectives. Journal of European Integration 28 (1): 7–31.

Thorhallsson, B., and Steinsson, S. 2017. Small State Foreign Policy. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics.

Tønnesson, S. 2015. Deterrence, Interdependence, and Sino–US Peace. International Area Studies Review 18 (3): 297–311.

Wæver, O. 2017. International Leadership after the Demise of the Last Superpower: System Structure and Stewardship. Chinese Political Science Review 2: 452–476.

White, H. 2012. The China Choice: Why We Should Share Power. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Wood, B. 1987. Middle Powers in the International System: A Preliminary Assessment of Potential. Ottawa: North–South Institute. URL: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/WP11.pdf.

Vital, D. 1967. The Inequality of States: A Study of the Small Power in International Relations. Clarendon Press.

Yang, C. 2005. Great Power Relations and Asia-Pacific Security. Global Change, Peace & Security 17 (3): 291–298.

Yılmaz, Ş. 2017. Middle Powers and Regional Powers. Oxford Bibliographies: International Relations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zheng, H. 2020. Fragile Interdependence: The Case of Russia-EU Relations. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 33 (1): 50–70.