The Causal Relation-ship between Remittances and Poverty Reduction in Developing Country: Using a Non-Stationary Dynamic Panel Data

Journal: Journal of Globalization Studies. Volume 6, Number 1 / May 2015

The aim of this article is to investigate the causal relationship between re-mittances and poverty reduction for 14 emerging and developing countries over the period from 1980 to 2012. We proposed a cointegration analysis, using the method of non-stationary dynamic panel data. Our estimation re-sults reveal that causality nexus of poverty and remittances is bi-directional. We also find that the causal impact of poverty reduction on remittance is stronger than the reverse impact. Indeed, despite of its weak impact on the poverty, remittances should be taken seriously, and this by taking measures by developed countries to facilitate the access of immigrants to their territories. Such an initiative could reduce to some extent the inequalities within developing countries.

Keywords: remittances, poverty, developing countries, cointegration, dynamic panel, causality.

Introduction

John Donne's famous saying ‘no man is an island upon himself’ is even more relevant today than it was in 1624 especially in the world of international trade, globalization, international treaties and the United Nations. We live in an age of transnationalism, where transnational legal norms move around the globe Globalization and the increasing movement of capital and labor across international borders, with the exception of migrant workers who are facing major obstacles by immigration laws, are creating a situation where laws in general and labor laws in particular are obtaining an international character. Internationally the problem of movement of labor is the asymmetric structure between capital and labor in reference to the freedom of movement. In view of increasing globalization, the Conventions of the International Labor Organization (hereafter the ILO) have assumed greater prominence in recent years. Internationalization and globalization have had a growing impact in many areas especially in legal and economic relations (Smit 2010).

There has been a rapid growth in the role of international agreements and supranational authority over the past 40 years that regulate economic, social, communications, environmental and human rights behavior (Simmons 1998). Transnational relations influence world politics in almost every issue-area. Many multi-national corporations with subsidiaries in other countries have annual financial turnovers larger than the gross national product (GNP) of several countries, and create adaptation problems for the foreign economic policies of many states (Risse-Kappen 1995). The original concept of transnational relations encompasses almost everything in world politics, except inter-state relations. This has led to a situation where many sovereign nation-states were forced to choose a side in establishing their political, economic, social, and cultural relations and operations, which, in itself, again led to regionalism.

The SADC Region has a total population of about 280 million and is considered to be one of the most promising developing regions in the world in terms of economic potential (Mukuka 2013). Almost 40 per cent of the region's population still lives in conditions of abject poverty which translates to a need of a sustained economic growth in the region of around six per cent per annum. This paper is premised on the conviction that the successful implementation of SADC policies, objectives as found in the SADC Treaty, Charter and protocols through appropriate employment and labor policies as well as strategies can contribute towards regional integration, regional labor standards, improvement in the quality of life of millions of people and the attainment of sustained growth that are required to alleviate and subsequently eradicate the unacceptably high levels of poverty in many SADC member states, it is, therefore, not necessary to re-invent the wheel. Unfortunately, the average citizen within SADC does not see or experience in practical benefit in all these policy documents (Smit 2014).

The purpose of this paper is, therefore, to analyze the theoretical framework of transnational labor relations and regional labor standards and what motivates countries to adhere or not adhere to transnational law. An overview of SADC and its institutional architecture is also provided. The SADC Charter, its origins and link to ILO core conventions are analyzed and the author illustrates how these instruments can contribute towards SADC regional integration and the establishment of a transnational labor relations system within SADC. The author suggests that a transnational labor relations system within SADC is attainable by just adhering to the ILO core conventions and the SADC Charter but that the practical problem lies with compliance and monitoring such. An overview of the concept of globalization is provided and the author argues that in the greater scheme of things the transnational labor relations can contribute towards regional integration and this in turn creates a framework for regional globalization. The possibilities for further research are also indicated.

Conceptualizing Transnational Labor Relations and Regional Labor Standards

Hyman defined labor relations as the regulation of work and employment and it involves different forms of collective regulation which refract and transform the merely monetary dynamics of the employment relationship (Hyman 2001). The living and working conditions of most working people and thus of society as a whole are determined by the nature and quality of labor relations (Kohl and Platzer 2003).

The development of a proficient labor relations system is as much an intrinsic part of a system change as it is a requirement for successful transformation seeing that they are primary components of civil society and can provide indispensable guidance for the resolution of social conflict, forming harmonies, economic modernization and the stabilization of social equality.

Initially labor relations emerged on a confined or sectoral basis, but it became consolidated within a national institutional structure (Hyman 2001). It is important that national labor relations systems must not be understood in isolation, but within a framework or structure to understand a global labor relations framework that is growing and developing (Lillie and Lucio 2012).

Transnationalism can be viewed as the shared, educational, political and economic associations and interactions that take place between people and institutions. Labor markets on the other side become transnational if they involve activities and occupations that require regular and sustained social contacts over time across national borders for their implementation (Horvath 2012). Transnationalism can also be seen as an escalating, deepening process in which innovative social practices, systems of symbols and objects come about through increasing international movement of goods, information and people. New transnational forces of capital and labor have surfaced as important actors as a result of the transnationalization of production and funding in times of global restructuring (Bieler 2005).

Transnationalism and all its different facets have a major influence on all the different role players in Transnational Companies (TNCs) and especially the employment relationship. Not only does a TNC need to integrate various human resource principles and policies to create cohesion (Dickmann, Müller-Camen, and Kelliher 2008), but also have to implement transnational human resource management (THRM) practices (Gennard 2008).

It becomes problematic where employment or labor decisions that are taken in one area of the world have an effect on employment relations somewhere else in the world. It is apparent that transnational relationships of actors have become so intertwined that it is almost impossible to understand the strategies of actors within one country without referring to the events and strategies of actors in other countries (Lillie and Greer 2007). It would seem as if transnational capital plays national environments of against each other but at the same time attempts to create a genuinely global business environment (Lillie and Lucio 2012). The globalization of markets and firms has had a profound impact on labor relations (Greer and Hauptmeier 2008) and defined Labor transnationalism as ‘The spatial extension of trade unionism through the intensification of co-operation between trade unionists across countries using transnational tools and structures’.

Research on labor transnationalism is becoming more important due to the rapid growth in TNCs. Political entrepreneurs can play a vital role in the development of labor transnationalism. Political entrepreneurs should have the vision to look at transnational strategies and the leadership skills to impact on their own constituencies. International (or global) framework agreement (IFA) which is an instrument negotiated between a multinational enterprise and a Global Union Federation (GUF) in order to establish an on-going relationship between the parties and ensure that the company respects the same standards in all the countries where it operates also impacted on the research on labor transnationalism.

Helfen and Fichter are of the opinion that ‘academic research is only beginning to deal with what we would define as an emerging arena of transnational labor relations’ (Helfen and Fichter 2013).

The rise and growth of the EU are the landmarks of a development process that involved the globalization of capital and trade that resulted in the establishment of a new transnational regulations system as well as the reformation of general economies and welfare states. It is on this basis that different forms of transnational labor relations and or regional labor standards have emerged (Horvath 2012).

It would appear that transnational labor relations are still in an emerging, formative phase considering institutionalization, projecting a very fragmented, diverse and mixed picture of development even though certain processes and institutions. European Works Councils have emerged within the EU that strongly suggests that the EU is on the way to the establishment of the EU transnational labor relations regime or regional labor standards. Lillie and Lucio have identified that there are two dominant trends in transnational labor relations research; namely, the optimists who show how it can work in specific situations, and then there are pessimists who stress labor's vulnerability against management-devised competitive frameworks (Lillie and Lucio 2012).

The expansion of transnational labor relations and the establishment of regional labor standards would require trade unions to reassert their main objectives in a contemporary language so that they can effectively function in flexible labor markets and different workplaces (Taylor 1999). There are obvious obstacles that stand in the way of the development of a realistic and permanent transnational labor relations system as transnational trade union federations must decide on strategies to confront the countless challenges from increasing globalization. The development of transnational labor relations and regional labor standards are of great importance as it can assist organized labor to mobilize and enhance its power through international agreements across national borders.

Transnational Law

To understand the general structure of the world's industrial relations system, the role of regional powers and transnational actors should be explained in order to perceive the influences of global challenges (Aliu 2012).

One can, therefore, rightly ask: What is ‘transnational?’ The term would indicate that it is beyond what is considered to be national, in other words, across national borders. Transnational law is the term commonly used for referring to laws that govern the conduct of independent nations in their relationships with one another. It differs from other legal systems in that it primarily concerns states, rather than private citizens. In other words, it is that body of law that is composed of the greater part of the principles and rules of conduct which states feel themselves bound to observe and, therefore, do commonly observe in their relations with each other. These include:

(a) The rules of law relating to the function of international institutions or organizations, their relations with each other, and their relations with states and individuals; and

(b) Certain rules of law relating to individuals and non-state entities, so far as the rights and duties of such individuals and non-state entities are the concern of the international community.

Transnational law can be equated with a Transnational Legal Process (TLP) which provides the key to understand the issue of compliance with international law. This view immediately raises the following question: why do nation-states and other transnational actors obey international law, and why do they sometimes disobey it? (Koh 1996) In order to answer this very important question three very obvious questions come to light, namely: what is a transnational legal process, where did it come from and how does it assist in explaining why nations obey?

Koh sees the transnational legal process as the manner in which theory and practice of public and private actors, nation-states, international organizations, multinational enterprises, NGO's and private individuals interact in a variety of private and public, international and domestic spheres and also how they interpret, enforce and then ultimately internalize the rules of international law. A TLP has four very distinctive features:

i. It is non-traditional.

ii. It is non-statist as it also includes non-state actors.

iii. It is very dynamic and not static.

iv. It is normative as it not only describes a process but also the normativity of that process (Koh 1996: 184).

It would appear that democracies are more likely to comply with international legal obligations, as they share an affinity with international legal processes and institutions. Countries with independent judiciaries are more likely to trust and respect international judicial processes and political leaders that are accustomed to constitutional constraints on their power in a domestic context are more likely to accept principled legal limits on their international behavior (Simmons 1998: 83–84). A transnational labor relations ‘regime’ would be a set of structures and norms operating across national borders to buttress national law and practices by either reinforcing national norms or superseding them (Trubek, Mosher, and Rothstein 2000: 1194). Chayes and Chayes contend that states enter into international agreements and that they will to a certain degree comply with those agreements on three propositions:

i. The propensity to comply is more plausible and useful than the assumption that states will violate treaties whenever it is in their interest to do so;

ii. Very often compliance problems do not reflect a deliberate decision to violate international agreements; and

iii. Complete or strict compliance of treaties is unnecessary and all that is required is an acceptable level of overall compliance to safeguard the interest of the treaty (Chayes and Chayes 1993).

Efficiency, interests, and norms all favour treaty compliance. This is mainly because decisions are not free, there is a continuous recalculation of costs vs. benefits and also international treaties are related to states interests as international law cannot bind states except with their own consent. As national positions and interests evolve it will help to induce compliance. The fundamental norm of international law is pacta sunt servanda – treaties are to be obeyed, the compliance with international treaties and law is, therefore, also a very important normative process.

Noncomplying behaviour can be attributed to the following factors:

i. Ambiguity and indeterminacy of treaty language as treaty language varies in its determinacy.

ii. Limitations on the capacity of parties to carry out their undertakings. Apart from a political will to comply, the choice that must be made domestically requires scientific and technical judgment which states, especially developing countries, may be lacking.

iii. All treaties require a period of transitions before mandated changes can be accomplished. Changing conditions and underlying circumstances require a shifting mix of regulatory instruments to which state behaviour cannot instantly respond. Treaties are not just ‘aspirational’, the ultimate goal is to start a process that will over time bring states into greater congruence with treaty ideals (Chayes and Chayes 1993).

The traditional model of industrial relations that are limited to the borders of nation-states is increasingly becoming problematic, with the opening of and merging of labor markets, of which the European integration process is a very good example (Seifert 2012). The market freedoms enshrined in the TFEU have contributed to building up an internal market on the European scale. Transnational enterprises can easily relocate their activities from subsidiaries in one country to those located to another country (Seifert 2012). Transnational collective bargaining in European-scale companies has gained increasing relevance over the last years due to the increasing number of European works councils (EWCs) that have been established. Jeremy Waddington describes EWCs as a Transnational Industrial Relations Institution in the making (Waddington 2012: 232). European trade unions are also trying to undertake transnational collective bargaining with European-wide companies with European Framework Agreements (EFA) (Seifert 2012). EWCs and EFAs have given a transnational character to the labor relations in the EU.

There seems to be an increasing support for the establishment of a legal framework for transnational collective bargaining within the EU. The use of international labor standards in domestic law must be based on the legal materials available to states under their domestic laws. These materials include international customary law, the manner in which a state's constitution articulates with international law. International labor standards provide a rich and authoritative source for the development of labor law and national level that can ensure consistency between the different systems of law and at the same time ensuring state compliance with international obligations (Cheadle 2012).

Establishment and Original Aims of SADC

Current members of SADC are Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, Republic of South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

SADC was originally founded in April 1980 as the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC) by the leaders of the so-called Frontline States in Southern Africa. The original aim was to create a mechanism whereby member-states could formulate and implement projects of common interest in select area in order to reduce their economic dependence, particularly, but not only on the Republic of South Africa. It was conceived as an economic dimension of the struggle of liberation from colonial and white minority rule and the economic domination of the sub-region by the apartheid regime in South Africa (Ngongola 2012).

The founders were clear that trade and market integration were not its priorities, the desire was for genuine and equitable regional integration. Trade liberalization and market integration became part of the SADC common agenda when SADCC became SADC under the Windhoek Declaration and Treaty of 1992. This treaty provided for Regional Economic Communities (RECs) for the different sub-regions of Africa and SADCC had to be repositioned as the REC for the Southern African sub region and by including South Africa as a member and prioritizing trade liberalization and market integration. A protocol on trade was signed by eleven member states, excluding Angola, in 1996, providing for the establishment of a free trade area (FTA). This protocol became into force in January 2000 when it was ratified by two thirds of the members (Ibid.).

SADC member states are encouraged to ensure the harmonization of political and socio-economic plans, to develop economic, social and cultural ties, to participate fully in the implementation of SADC projects, developing policies that can lead to the elimination of obstacles to the free movement of people, labor, capital, goods and services and to promote the development of human resources and also the development, transfer and mastery of technology. Eight areas of cooperation have been identified and each area is administered by a protocol. A protocol enters into force if it has been ratified by at least two thirds of the member states and a protocol is only binding on a member state that has ratified it (Ngongola 2008).

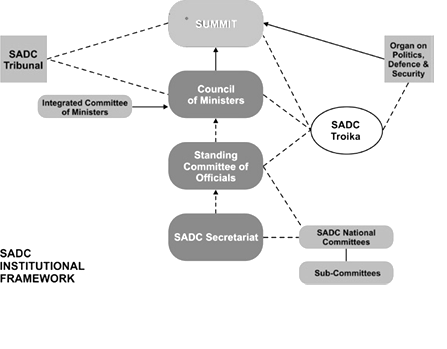

The institutional architecture of SADC can be illustrated schematically as follows.

Fig. 1. The institutional architecture of SADC

Source: Peters-Berries 2002.

The main sections within the SADC institutional framework are described below.

1. Summit

The Summit is made up of all SADC Heads of States or Government and meets twice a year. The Summit is the ultimate policy- and decision-making body of SADC, responsible for policy direction and the SADC's overall control functions.

2. Council of Ministers

The Council of Ministers consists of Ministers from Foreign Affairs and Economic Planning or Finance of all member states. The Council oversees the functioning and development of SADC and ensures that SADC's policies are properly implemented. It is the Council's responsibility to manage SADC's affairs and to advice the Summit on matters of overall policy. The Council is the second highest level of authority and the highest functioning level in SADC and meets four times a year.

3. Standing Committee of Officials

The Standing Committee of Officials, a technical advisory committee to the Council of Ministers, meets twice a year. It consists of one Permanent/Principal Secretary, or an official of equivalent rank from each member state, preferably from a ministry responsible for economic planning or finance.

4. Secretariat

This is the principal executive body of SADC. The Secretariat is responsible for the day-to-day activities, co-ordination, strategic planning, and management.

5. Tribunal

The Tribunal, which is no longer functional, was established in Windhoek, Namibia with the signing of a protocol during the 2000 Ordinary Summit. The main aim for the establishment of the Tribunal was to ensure adherence to and implementation of the provisions of the SADC Treaty and Contributory instruments. Article 15 of the Treaty states that the Tribunal also has jurisdiction over disputes. The Tribunal derives its power and legal status from the SADC Treaty.

The institutional framework of the organization was previously oriented on a cooperative, and not on an integration approach. For this reason institutional challenges remain. There is still a huge gap between SADC regional initiatives and the member states' national objectives. Regional integration is high on the priority list of SADC and the initial agenda was to establish a Free Trade Area in 2008, a Customs Union in 2010, a Common Market in 2015, a Monetary Union in 2016 and regional currency in 2018. This regional integration agenda is very ambitious under the current environment and it is clear that it is not achievable. Some progress has been made towards the establishment of a Free Trade Area and a Customs Union but there still major differences between member states regarding the implementation.

SADC Charter on Fundamental Social Rights

The overall objective of the Fundamental Social rights in SADC Charter is to facilitate through close and active consultations amongst social partners, a spirit conducive to harmonious labor relations within the region.

The Southern Africa Trade Union Co-Ordination Council (SATUCC) played a major role in the drafting and eventual acceptance by the SADC Employment and Labor Sector (ELS) thereof in 2001.

SATUCC represents all major trade union federations within the Southern African region and was initially launched in March 1983 in Gaborone, Botswana (LaRRI 2001). Some of the main aims of SATUCC were:

i. to co-ordinate union activities in the region;

ii. to contribute towards economic and social liberation of the region;

iii. to develop democratic and free trade unions and to assist the oppressed black trade unions, at that stage in South Africa and Namibia; and

iv. to intensify worker education on matters related to social security and international labor standards.

In January 1995, the SADC Council of Ministers decided to create a new SADC Employment and Labor Sector (ELS) and SATUCC was recognized as the representative regional trade union body. As time went by SATUCC became politically visible and were reporting on economic and employment conditions and were also making suggestions to SADC (LaRRI 2001). The trade union movements within SADC were concerned that the economic focus of SADC states had overridden the political aspirations of regional integration. Several workshops were organized by SATUCC to address amongst other issues, the following:

i. the development of a plan to regulate the free movement of labor within SADC until greater economic equality is achieved;

ii. the role unions can play within SADC to ensure that minimum labor standards apply to all workers;

iii. the need for an integrated policy of industrial and human resource development; and

iv. the development of a Social Charter with minimum labor standards that should be applied to protect workers.

The Social Charter was adopted by SATUCC and presented to the Southern African Labor Commission (SALC) in Lusaka in March 1992 and was also further discussed at the SALC Conference in Maseru in 1995 (LaRRI 2001). The Charter was also discussed by the ELS of SADC over many years. Initially governments were reluctant to adopt the Charter and many disagreed with the idea of free movement of people in the region, employers also delayed the adoption and demanded that the right to lock-out should be entrenched as a basic right. In an effort to reach consensus amongst governments and employers the Charter went through several changes over the years. The Charter of Fundamental Social Rights in SADC was finally adopted at the ELS meeting of SADC in Windhoek in February 2001.

In 2003, the Council of Minister of SADC adopted the Charter on Fundamental Social Rights which amongst others seeks to provide a framework for regional labor standards. It obliges member states to create an enabling environment, consistent with ILO core conventions, to prioritize ILO core conventions and take the necessary action to ratify and implement these standards. The Charter further requires member states to create an enabling environment to ensure equal treatment for men and woman, and for the protection of children and young people (Van Niekerk et al. 2012).

Unfortunately, the Charter cannot be enforced directly, and unlike ILO Conventions there is currently no independent supervisory mechanism to call members to account for any breach of the Charter.

The main objectives of this Charter are to:

1. Ensure the retention of the tripartite structure of the three social partners, namely: governments, organizations of employers, and organizations of workers.

2. Promote the formulation and harmonization of legal, economic and social policies and programs, which contribute to the creation of productive employment opportunities and generation of incomes, in member states.

3. Promote labor policies, practices and measures, which facilitate labor mobility, remove distortions in labor markets and enhance industrial harmony and increase productivity, in member states.

4. Provide a framework for regional co-operation in the collection and dissemination of labor market information.

5. Promote the establishment and harmonization of social security schemes.

6. Harmonize regulations relating to health and safety standards at work places across the Region; and

7. Promote the development of institutional capacities as well as vocational and technical skills in the Region.

It is also important to pay attention to some of the most important articles of the charter that relate directly to labor relations and labor standards.

The article on universal and basic human rights as proclaimed by the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, Constitution of the ILO and the Philadelphia declaration are to be observed (Art. 3).

The article on Freedom of association and collective bargaining requires member states to create an enabling environment consistent with ILO Conventions on freedom of association, and the right to organize and collective bargaining (Art. 4). SATUCC is of the opinion that this right should be entrenched in the Constitution of every individual member state of SADC.

The article on the Conventions of the International Labor Organization (Art. 5) requires member States to establish a priority list of ILO Conventions which shall include Conventions on abolition of forced labor (Nos. 29 and 105), freedom of association and collective bargaining (Nos. 87 and 98), elimination of discrimination in employment (Nos. 100 and 111), and the minimum age of entry into employment (No. 138). Member states must take the necessary steps, as a priority, to ratify and implement the core ILO Conventions.

The article on the Equal treatment of men and women requires that men and women must be treated as equals in all aspects of the work life (Art. 6).

The Protection of children and young people in line with ILO Convention 138 deals with employment age, remuneration of children and young people and vocational training (Art. 7).

The issues of Elderly people, retirement age and social benefits for elderly people who do not have a pension but have reached normal retirement age are also addressed (Art. 8).

The treatment of Persons with disabilities in the work place and their access to training and social security are contained in Article 9 of the Charter.

All employees will have access to Social protection and social security benefits and social assistance irrespective the type of employment (Art. 10).

All member States must strive towards the Improvement of living and working conditions of employees by addressing issues like working hours, rest periods, paid leave and maternity leave etc. (Art. 11).

Every employee in SADC has the right to a healthy and safe working environment (Art. 12).

Member States are also required to create an enabling environment so that industrial and workplace democracy is promoted (Art. 13).

From the above it is clear that the Charter aims at creating or establishing a broad framework of basic labor and/or social rights and this can be interpreted as a Transnational Labor Relations framework for SADC.

Member states are required to submit regular progress reports to the Secretariat regarding the implementation of the Charter. Unfortunately, the Charter does not specify what is meant by regular reports nor what steps can be taken against a member state that fails to implement the Charter.

Status of ILO Core Conventions in Member States of SADC

It is also important to establish the link between ILO Core Conventions and the SADC Charter as both these instruments can assist in the establishment of regional labor standards which ultimately can play a part in the process of regional integration.

In 1998, the ILO adopted the Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work it is an expression of commitment by governments, employers' and workers' organizations to uphold basic human values – values that are vital to our social and economic lives. The Declaration commits Member States to respect and promote principles and rights in four categories, whether or not they have ratified the relevant Conventions.

These categories are:

i. freedom of association including the right to collective bargaining;

ii. the elimination and prohibition of forced or compulsory labor;

iii. the abolition and prohibition of child labor; and

iv. the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

The ILO Declaration of 1998, thereby makes these core Conventions binding on member states irrespective if these Conventions have been ratified or not. There is currently a discussion within the ILO to include the Conventions on health and safety as well as the Convention on a living wage as part of the core labor rights.

Article 5 of the SADC Charter requires member States to establish a priority list of ILO Conventions and specifically to ratify and implement the core conventions of the ILO.

The table below indicates the 15 member States of SADC and in which year a particular core convention of the ILO has been ratified.

Table 1

| Member | C29 | C87 | C98 | C100 | C105 | C111 | C138 | C182 | ||

| Angola | 2001 | 1976 | 1976 | 1976 | 1976 | 1976 | 2001 | 2001 | ||

| Botswana | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 | 2000 | ||

| DRC | 2001 | 1969 | 1960 | 2001 | 1969 | 2001 | 2001 | 2001 | ||

| Lesotho | 1966 | 1966 | 1966 | 2001 | 1998 | 1998 | 2001 | 2001 | ||

| Madagascar | 1960 | 1960 | 1998 | 1962 | 2007 | 1961 | 2000 | 2001 | ||

| Malawi | 1999 | 1965 | 1999 | 1999 | 1965 | 1965 | 1999 | 1999 | ||

| Mauritius | 2005 | 1969 | 1969 | 1969 | 2002 | 2002 | 1990 | 2000 | ||

| Mozambique | 1996 | 1996 | 2003 | 1977 | 1977 | 1977 | 2003 | 2003 | ||

| Namibia | 1995 | 1995 | 2000 | 2000 | 2010 | 2001 | 2000 | 2000 | ||

| Seychelles | 1978 | 1999 | 1978 | 1978 | 1999 | 1999 | 2000 | 1999 | ||

| South Africa | 1996 | 1996 | 1997 | 1997 | 2000 | 1997 | 2000 | 2000 | ||

| Swaziland | 1978 | 1978 | 1978 | 1979 | 1981 | 1981 | 2002 | 2002 | ||

| Tanzania | 2000 | 1962 | 1962 | 1962 | 2002 | 2002 | 1998 | 2001 | ||

| Zambia | 1996 | 1996 | 1964 | 1965 | 1972 | 1979 | 1976 | 2001 | ||

| Zimbabwe | 2002 | 1998 | 1998 | 1998 | 1989 | 1999 | 2000 | 2000 | ||

It is argued that the SADC Charter of Fundamental Social Rights and the seven core ILO conventions that have been ratified by all member states of SADC can form the basis of a Transnational Labor Relations system and or regional labor standards in SADC. The main aims of the SADC Charter will not be achieved in as far as it concerns the place of work and employees if these core ILO Conventions have no real impact on the shop floor and the life's of employees. It is also clear that when SATUCC started its campaign for the establishment of the SADC Charter that the core ILO conventions formed the basis of the proposed content of the SADC Charter. The core ILO conventions have created an international obligation on ILO member states and the SADC Charter aims to establish a further regional obligation on SADC member states.

Regional Integration vs. Regional Globalization

Is Regionalism just a different form of globalization, or are these two terms or ideas compatible? Globalization can be defined as a process by which the economies of the world become increasingly integrated leading to a global economy with global economic policy making, through such international agencies as the World Trade Organization (WTO). Globalization is also viewed by many as a ‘global culture’ in which the world population consumes similar goods and services across countries and use a common business language, English. This has led to an increase in the openness of economies to international trade, financial flows and direct foreign investment. Globalization can lead to an increase in the mobility of factors of production mainly capital and labor (Kamau 2013). Many people view globalization as Americanization.

Economic integration occurs whenever a group of nations in the same region join together to form an economic union or regional trading bloc by raising a common tariff wall against the products of non-member countries while freeing internal trade among members. The integration provides an opportunity for industries to take the advantage of economies of large-scale production made possible by the expanded markets. A regional economic bloc should, therefore, be conceptualized as an entity encompassing and transcending nation-states. The economic aspect of these may be described as, in the first instance, the efforts to form free-trade zones through the creation of common markets, and secondly, the co-ordination of economic policies and the implementation of joint economic policies to form even larger economic zones. Regionalism has had enormous impact on the environment of nation-states. It has, for instance, had a regulating impact on MNCs through measures such as corporate laws, competition policies, and labor policies. The very essence for the creation of a regional economic organization is to give them greater ability to protect regional and national interest in relation to other countries, transnational companies and international economic organizations. This contradicts globalization (Yeates 2005).

Regional formations are an important manifestation of state strategies and integral to any analysis of the ways in which collective action is recast at a transnational level. The main of most regional formations are economic by nature. The almost exclusive preoccupation of these formations with economic issues has led to a reaction from international civil society organizations, which increasingly demand that social issues be addressed as well. Yet, civil society demands are articulated through the shadow summits and social forums that now regularly accompany intergovernmental meetings. This lays the groundwork for the development of an inclusive, democratic and developmental social policy at regional level; in this regard the SADC Charter is a very good example.

Social welfare, social institutions and social relations have become entangled in material processes that extend beyond national borders and their transformation now has a regional character (Kamau 2013). These transnational elements and the dynamics that come with it must begin with an appreciation of the contemporary pluralistic global social governance structure which is ‘multi-tiered’, ‘multi-sphered’ and ‘multi-actored’.

The regional integration strategy of SADC and other regional formations can be found in transnational collaboration, which can include: exchange of information; identification of common issues and positions; collaborative action on specific issues; coordination of national laws, policies and practices; coordination of policy positions; and collective representation at other regional or international forums. But is this regional globalization?

Regional formations are an integral part of any critical assessment of the possibilities for transformative political agency in a globalization context. Regional formations are very often the result of political struggle and negotiations over the content and direction of a social policy that reflects the traditions, interests and needs of member countries and their populations.

Regional agreements in actual fact discriminate against third countries outside the region and become protectionist blocs with their own sets of trade rules. Politically, regional formations can offer member countries a number of advantages. They facilitate governments in the achievement of their foreign policy objectives. Regional formations can also act as a mechanism and a selective approach to the construction of political collaboration. Since regional formations often entail groups of countries with similar cultural, legal and political characteristics, agreement on the scope and nature of transnational collaboration is more feasible and progress can potentially proceed more quickly than multilateral negotiations, this is, however, not the case with SADC.

The proliferation of regional formations indicates a willingness on the part of governments to commit themselves to collaboration around trade issues, but these commitments have (so far) only in a limited capacity extended to collaboration around social welfare or developmental needs for the particular region. Most regional formations reflect the present preoccupation with narrow commercial objectives over broad social developmental needs. Phrases like ‘inclusion’, ‘democracy’ and ‘development’ can be found in some regional formations' social policy objectives.

The formulation of policies that encourage intra-regional trade and offer barriers to external trade, as founded in most regional formations contradicts the view of the proponents of globalization which are geared towards free movement of the factors of production on a global scale not limited to regions. Regional formations can reduce global trade and obviously reduce efficiency in the market with trade tariffs and is seen by many to reduce competitiveness and renders market forces almost irrelevant which eventually lead to gross market inefficiencies (Yeates 2005).

Regional integration restricts sovereignty of member states in economic policy formulation to a certain degree but has a number of advantages including an increased specialization and realization of economies of scale through the pooling of resources and markets, increased choice through access to wider range of markets and increased competitiveness of goods and services in global markets following the development of intra-regional competition. Regionalization can also lead to better opportunities for scientific and engineering exchange and joining efforts to develop science and technology as well as the creation of better infrastructure in transport, finance and communications (Ibid.).

It is clear that there are certain similarities but also differences between globalization and regionalization. These two concepts are not completely compatible but neither are they totally incompatible. The apparent incompatibility of regionalism and globalization withstanding, it is impossible to see a globally integrated system with the ever increasing and stronger regional trading blocs, many with conflicting objectives, approaches and even mechanisms.

Conclusion and Recommendations

If a system of regional labor standards is established for SADC, it must take cognizance of the differences between countries in terms of culture, language, history, the legal system, etc. The system that has been designed for the EU and that is currently in place is a uniquely European system and cannot be transferred to SADC as it is. SADC must not try to replicate the EU system of regional labor standards. The proposed system of transnational labor relations for SADC should be a combination of the following:

1. The SADC Treaty, certain SADC protocols, and the SADC Charter should be adapted, extended, and strengthened to make provision for minimum regional labor standards. This treaty on minimum regional labor standards should include, as a bare minimum, requirements of the ILO core standards, the UN declaration of Human Rights, and employees' rights at work. The domestic incorporation of the SADC Treaty, SADC Charter and SADC protocols into national laws can ensure ease of compliance by member states.

2. A code of best practices for TNCs should be established, providing minimum labor standards for any TNC that wants to establish business enterprises in any SADC member state.

3. The local actors in all SADC member states should be empowered through a process of training, so as to provide them with the necessary skills, knowledge, and expertise to create public awareness of human rights, social rights, and labor rights. The local actors in each member state can play a significantly positive role in ensuring that governments adhere to the minimum regional labor standards.

4. An independent monitoring system that brings governments, employers, TNCs to task for failure to comply with minimum regional standards should be established. The SADC Tribunal should become operational as soon as possible, and its mandate should be extended so that it can also act as a labor standards watchdog. The new Tribunal should have the power to take appropriate steps against not only employers or TNCs, but also against governments. These powers can include imposing fines on transgressors.

A transnational labor relations system for SADC is for all practical purposes already in existence, and it can assist in providing certain minimum protections and labor rights for millions of people. The SADC Charter, which has been signed by all member states and the ILO core conventions that have been ratified by all member states, provides the basis of a TNLR system in SADC. For this system to be of any real value it is of the utmost importance to involve all role players from all the member states. These must include not only governments and politicians, but also employers' associations, trade unions, and other local actors. Rules are needed at the appropriate levels, so that economic principles and justice go hand in hand, and the standards and the issues at stake have a transnational or supra national character. Thus, SADC must have its own, unique social policy and, consequently, also its own fully fledged labor relations system. SADC must move away from a facilitating authority to an entity that will lead in creating standards and mechanisms that can be of benefit to all SADC citizens and become a truly transnational actor and in this regard the SADC Charter must form the basis.

The possibilities for further research are almost endless. The content, character and impact on grass root level of the labor laws within each member states can be evaluated and measured against the SADC charter as well as the ILO core conventions. It is also possible to establish a regional Labor Tribunal for SADC that specifically deals with labor relations issues and transnational collective bargaining; this in itself will require further research and will have to involve all member states as a political decision will have to be taken by the Summit of SADC.

The regional integration strategy of SADC as founded in the Treaty and Charter as well as other protocols can only be achieved in the SADC region if there is closer co-operation between member states on matters like social policy and labor standards. This will lead to the improvement of the work life of millions of people. Regional formations or regional integration schemes are not regional globalization.

REFERENCES

Aliu, A. 2012. European Industrial Relations: Transnational Relations and Global Challenges. Munich Personal RePEc Archive (MPRA). URL: http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/38897/.

Bieler, A. 2005. European Integration and the Transnational Restructuring of Social Relations: The Emergence of Labour as a Regional Actor? Journal of Common Market Studies 43(3): 461–484.

Chayes, A., and Chayes, A. H. 1993. On Compliance. International Organization 47(2): 175–205.

Cheadle, H. 2012. Reception of International Labour Standards in Common-law Legal Systems. Reinventing Labour Law 348–364.

Dickmann, M., Müller-Camen, M., and Kelliher, C. 2008. Exploring Standardization and Knowledge Networking Processes in Transnational Human Resource Management. Personnel Review 38(1): 5–25.

Donne, J. 1624. Mediations XVII. Devotions upon Emergent Occasions and Several Steps in my Sickness s.p. URL: http://www.online-literature.com/donne/409. Accessed 20 Jan. 2014.

Gennard, J. 2008. Negotiations at Multinational Company Level? Employee Relations 30(2): 100–103.

Greer, I., and Hauptmeier, M. 2008. Political Entrepreneurs and Co-Managers: Labour Transnationalism at Four Multinational Auto Companies. British Journal of Industrial Relations 46: 76–97.

Helfen, M., and Fichter, M. 2013. Building Transnational Union Networks across Global Production Networks: Conceptualising a New Arena of Labour-Management Relations. British Journal of Industrial Relations 51(3): 553–576.

Horvath, K. 2012. National Numbers for Transnational Relations? Challenges of Integrating Quantitative Methods into Research on Transnational Labour Market Relations. Ethnic and Racial Studies 35(10): 1741–1757. URL: http://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com. Accessed 20 Nov. 2013.

Hyman, R. 2001. The Europeanisation or the Erosion of Industrial Relations? Industrial Relations Journal 32(4): 280–294.

Risse-Kappen, T. 1995. Bringing Transnational Relations Back in: Non-state Actors, Domestic Structures, and International Institutions. Cambridge Studies in Industrial Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koh, H. H. 1996. Transnational Legal Process. Nebraska Law Review 75: 183–186.

Kohl, H., and Platzer, H. W. 2003. Labour Relations in Central and Eastern Europe and the European Social Model. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 9(1): 11–30.

Labour Resource and Research Institute (LaRRI) 2001. Building a Regional Labour Movement: The Southern Africa Trade Union Co-ordination Council 10.

Lillie, N., and Greer, I. 2007. Industrial Relations, Migration, and Neoliberal Politics: The Case of the European Construction Sector. Politics and Society 35(4): 551–581.

Lillie, N., and Lucio, M. M. 2012. Rollerball and the Spirit of Capitalism: Competitive Dynamics within the Global Context, the Challenge to Labour Transnationalism, and the Emergence of Ironic Outcomes. Critical Perspectives on International Business 8(1): 74–92.

Mukuka, J. 2013. Draft SADC Protocol on Employment and Labour adopted in Maputo. Lusaka Voice. URL: http://lusakavoice.com/2013/05/19/draft-sadc-protocol-on-employment-and-labour-adopted-in-maputo/.

Ngongola, C. 2008. The Legal Framework for Regional Integration in the Southern African Development Community. University of Botswana Law Journal 8: 3–46.

Ngongola, C. 2012. SADC Law: Building Towards Regional Integration. SADC Law Journal 2(2): 123–128.

Peters-Berries, C. 2002. Regional Integration in Southern Africa – A Guidebook. The Millennium Development Goals. Berlin: International Institute for Journalism.

Seifert, A. 2012. Transnational Collective Bargaining: The Case of the European Union. In Malherbe, K., Sloth-Nielsen, J. (eds.), Labor Law into the Future: Essays in Honour of Darcy du Toit (pp. 79–96). Jutalaw.

Simmons, B. A. 1998. Compliance with International Agreements. Annual Review of Political Science 1: 75–93.

Smit, P. 2010. Disciplinary Enquiries in Terms of Schedule 8 of the Labor Relations Act 66 of 1995. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of Pretoria. Pretoria.

Smit, P. 2014. Transnational Labour Relations in SADC: Dream or Possibility? African Journal of International and Comparative Law 22(3): 448–467.

Taylor, R. 1999. Trade Unions and Transnational Industrial Relations. Labor and Society Programme, DP/99/1999. Geneva: ILO.

Trubek, D. M., Mosher, J. and Rothstein, J. S. 2000. Transnationalism in the Regulation of Labor Relations: International Regimes and Transnational Advocacy Networks. Law and Social Inquiry 25(4): 1187–1211.

Van Niekerk, A. (Ed.), Christainson, M. L., McGregor, M., Smit, N., and Van Eck, B. P. S. 2012. Law Work. 2nd ed. LexisNexis: Durban.

Waddington, J. 2012. European Works Councils: A Transnational Industrial Relations Institution in the Making. London and New York: Routledge.

Yeates, N. 2005. ‘Globalization’ and Social Policy in a Development Context. Regional Responses, Social Policy and Development. Programme Paper no 18. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD).