Toward Optimization of Global Demographic Processes

Almanac: History & Mathematics:Political, Demographic, and Environmental Dimensions

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/978-5-7057-6354-2_07

Abstract

The present paper analyzes one of the most important factors in world development – the dynamics of global demographic growth, which demonstrates that the fears of uncontrolled population growth expressed in the framework of the report to the Club of Rome ‘Limits to Growth’ were partially justified and were typical for the period before the 1980s. However, statistical evidence after more than half a century demonstrates that the situation has changed and in the 1960s and early 1970s there was a peak of global demographic growth, after which a slowdown began. According to the UN forecasts, by the end of this century the population of the Earth will reach its peak, and its decline will begin. The authors provide an explanation for the change in the dynamics of the global demographic transition – most of economically developed states and a significant part of developing countries have moved to the second phase of the demographic transition, in which the birth rate falls to a level corresponding to a simple replacement of generations or below that level. At the same time, a new problem has arisen associated with a decline in fertility to the ‘lowest-low’ level – a tendency is formed to the negative natural population change in many countries, which is sometimes compensated by migration processes. Along with that, the process of population aging is developing in many countries of the world with an increase in life expectancy (LE) alongside low fertility. The indicated trends in the stabilization of the world population occur unevenly, with a fairly significant number of countries (mainly the countries of Tropical Africa) in which the second phase started not long ago, and fertility rates are still very high. At the same time, there is an acceleration of urbanization of the population in many developing countries. The paper also notes mutual influence of demographic processes and developments in various spheres of society and provides scenarios for their possible subsequent evolution, highlighting as a possible optimum scenario in which the stabilization of the Earth's population will reduce the degree of negative anthropogenic impact on the environment, but will also avoid a significant global depopulation. Given the unevenness of demographic processes, different approaches to stabilization have been noted: stimulating birth rate in countries with the lowest-low fertility and acceleration of fertility transition in the countries with very high birth rates.

Keywords: demographic models, historical demography, population growth, demographic transition, depopulation, fertility, Africa.

1. Current Situation

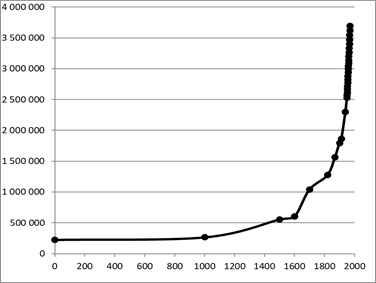

Malthusian fears reflected in the first report to the Club of Rome The Limits to Growth (Meadows et al. 1972) at that time were fully justified, since they were based on the analysis of statistical data since 1900. To better understand the situation and solid reasons for such apprehensions, it appears appropriate to consider the dynamics of world population growth over a longer period, fr om the beginning of our era to 1970 (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Dynamics of the world population from the beginning of our era to the mid-20th century (thousands)

Source: Maddison Project 2020.

We can infer from Fig. 1 that the demographic dynamics in the period from the beginning of our era to the mid-20th century is not exponential, but hyperbolic. This was first noted by Heinz von Foerster and his colleagues in 1960 in their article ‘Doomsday: Friday, 13 November, AD 2026’ (von Foerster et al. 1960), wh ere the title of the article indicates the point of singularity obtained through a hyperbolic approximation of statistical data on the dynamics of the population of the Earth. Since the World3 model was based on the statistical data from the first half of the 20th century, which reflected rapid and ever-accelerating demographic and economic growth, it is natural that the inertial forecast according to the model inevitably led to the depletion of resources at the beginning of the 21st century and to a demographic collapse. At the same time, the authors of the report believed that the development of technologies was unable to rectify the situation and the most realistic way to prevent a collapse was a rapid and radical slowdown in demographic growth (decrease in the birth rate).

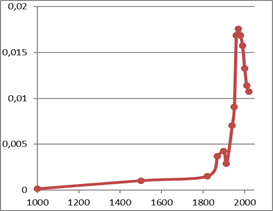

Sixty years have passed. What do the statistics show now? Fig. 2 presents a graph describing the dynamics of the relative annual growth rate of the Earth's population:

Fig. 2. Dynamics of averaged rates of the relative annual increase in the population of the Earth over the past 1,000 years

Source: Maddison Project 2020.

We can see that the maximum rate of demographic growth was observed in the 1960s and the early 1970s (i.e., 50–60 years ago). Since then, a steady decline has begun. Instead of the expected singularity, UN forecasts project a rapid deceleration of population growth and stabilization of the Earth's population by the end of the 21st century (UN Population Division 2022a, 2022b).

What are the causes for sharp fluctuations in the rates of demographic dynamics observed over the past 200 years? The fact is that during this period, global demographic transition has been taking place, and is now nearing its end (Kapitza 2006; Podlazov 2017; UN Population Division 2019, 2022b; Grinin and Korotayev 2015; Korotayev 2020b). Its first phase, associated with the transition of mortality from the traditional to the modern type (e.g., Chesnais 1992; Nath 2020), has already been passed by all countries of the world. As for the second phase, associated with the transition of fertility from traditional to modern type (e.g., Caldwell et al. 2006; Korotayev, Malkov, and Khaltourina 2006a), all economically developed countries, as well as a significant part of developing countries, have already passed it. On the other hand, a significant part of the developing countries, primarily located in sub-Saharan Africa, are still very far from completing the fertility transition, and fertility rates there remain very high (more than four children per woman) (see Grinin and Korotayev 2023; Korotayev et al. 2023; Zinkina and Korotayev 2014b; Korotayev and Zinkina 2014, 2015; Nzimande and Mugwendere 2018; Schoumaker 2019; May and Rotenberg 2020).

In most of the economically developed countries, fertility rates did not settle at the value corresponding to a simple replacement of generations (2.1 children per woman) after the completion of the demographic transition. Rather, these countries experienced a so-called second demographic transition from low to the lowest-low fertility (e.g., Lesthaeghe 2020). As a result, they show a steady trend towards depopulation, which in some first world countries is still offset by the migration increase (e.g., Vollset et al. 2020).

Another important consequence of the second demographic transition is the acceleration of global aging processes against the background of decreasing birth rate combined with an increase in life expectancy (LE) (see Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b). The process of global aging is currently more pronounced in the most developed countries, but it actually covers the entire world, which is evident from the increase in median age in all countries of the world (see Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b; Goldstone 2015; Goldstone et al. 2015; Zimmer 2016; Bengtson 2018; Fichtner 2018; Mitchell and Walker 2020).

As a result of the processes described above, the overall growth rate of the world population is currently slowing down (e.g., Korotayev 2020b). However, this process is very uneven. A large number of developed and developing countries (including Russia) are already experiencing absolute population declines (see Table; UN Population Division 2019, 2022a, 2022b; Vollset et al. 2020). At the same time most countries in Tropical Africa continue to experience exponential population growth, as demographic inertia there continues to compensate for some decline in the total fertility rate.[1]

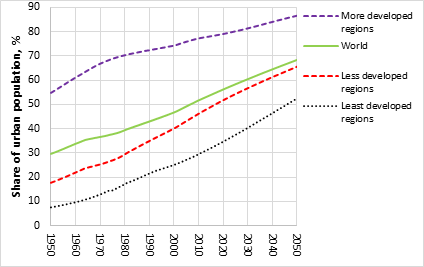

The processes of urbanization of the World System are unfolding rapidly. While in 1950 noticeably less than one-third of the world population lived in cities, already in the mid-2000s the share of city dwellers exceeded one half of all the people on the Earth, and by the middle of this century, according to the forecast of the UN Population Division (UN Population Division 2018), it will be noticeably more than two-thirds. At the same time, even in the countries of the World System core (according to the classification of Immanuel Wallerstein [1987]) only slightly more than one half of the population lived in cities in 1950. By 2050, the proportion of city dwellers there will approach 90 %. However, the growth rate of this share in the core countries will noticeably slow down as it approaches saturation, which apparently corresponds to this very level. In semi-peripheral countries, as early as 1950, only less than one-fifth of the population lived in cities, while by the mid-this century, this proportion will be about two-thirds. Finally, even in the countries of the World System periphery, more than one half of the population will live in cities, while in the middle of the last century this proportion was noticeably below 10 % (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Dynamics of the urban population share in the total population of the world and specific World System zones (empirical estimates for 1950–2020 with a forecast up to 2050)

Sources: UN Population Division 2018, 2022a.

2. Demography as a Factor in World Development

Demography is among the most important factors in the world development, as it exerts decisive influence on the main global socio-natural processes. In fact, population size is an ‘order parameter’ that determines the most important features of world dynamics at all phases of the global human history. Let us note some important interrelations of the demographic factor with other factors of historical development.

2.1. The Impact of Demography on Climate

The impact of population growth on climate is due to the growing anthropogenic impact on the environment, primarily due to an increase in CO2 emissions in the course of economic activity (see Akaev and Davydova 2023; Kovaleva 2023). In this regard, the projected slowdown in the growth of the Earth's population should have a stabilizing effect on the climate, which should intensify with a gradual transition to low-carbon (carbon-free) energy.

Reverse effect:

– global warming can have a significant impact on demographic dynamics, rather indirectly, through the growing problems of providing food to the population of Tropical Africa and South Asia, since these regions have not yet fully escaped the Malthusian trap (e.g., Korotayev and Zinkina 2015).

2.2. The Impact of Demography on the Environment

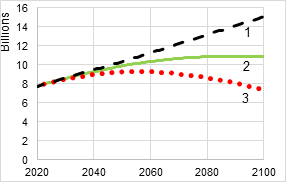

Population growth tends to increase CO2 emissions and the amount of waste (recyclable, non-recyclable, toxic), impact natural biocenoses in a negative way, and cause additional deterioration in the quality of the environment (air, soil, water bodies) (see Akaev and Davydova 2023; Kovaleva 2023). Respectively, the projected slowdown in the growth of the Earth's population should reduce the severity of environmental problems. However, it must be borne in mind that in the scenarios implying the most rapid decline in fertility, the scale of depopulation is rampant (see Table and Fig. 4), so it is necessary to look for a middle ground that would reduce the risks of environmental destabilization as much as possible, on the one hand, but, on the other hand, would prevent the risks of excessive depopulation.

Reverse effect:

– environmental degradation can have an impact on demography through a decrease in the quality of life and an increase in food problems, which are most critical in the countries of Tropical Africa and South Asia, since these regions have not yet fully escaped the Malthusian trap (e.g., Korotayev and Zinkina 2015).

2.3. The Impact of Demographics on Technology

For tens of thousands of years of human existence, demographic growth has had a powerful stimulating effect on the development of technology (Boserup 1965; Taagepera 1976, 1979; Kremer 1993; Tsirel 2004; Korotayev 2005, 2007, 2020a, 2020b; Korotayev, Malkov et al. 2006a, 2006b; Korotayev and Malkov 2016; Podlazov 2017; Grinin et al. 2020, 2022). In the long term, the global slowdown in population growth can be seen as one of the factors behind the slowdown in technological growth:

– there is a viewpoint suggesting that population ageing can also contribute to a slowdown in the pace of technological growth, but this issue requires further study, including taking into account the dynamics of perspective ages; population ageing can also lead to an acceleration in the development of medical technologies, as their costs will rise along with an increasing demand for such technologies (see Grinin and Grinin 2023; Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b; Grinin et al. 2017, 2020, 2022);

– in case of depopulation, a decrease in the number of working-age population can stimulate the development of labor-saving technologies.

Reverse effect:

– impact on fertility: expansion of contraceptives use leads to a decrease in unwanted births; the development of artificial insemination technologies contributes to an increase in the birth rate among older women;

– impact on mortality: the development of medical technologies leads to a decrease in mortality (including infant mortality) in developing countries and to a general increase in life expectancy (see Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b);

– impact on migration: on the one hand, the development of transport, information, communication, and financial technologies increases opportunities for migration; on the other hand, the development of remote work options contributes to the reduction of migration (see Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023a; Grinin et al. 2022).

2.4. The Impact of Demographics on Economy

Demographic dynamics affects changes in the labor force size (as a result of changes in the population age structure and migration processes) – in most countries it is expected to significantly decrease by the end of the century;

– changes in the population age structure cause changes in demand, as well as in the structure of budget expenditures (see Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b);

– changes in the age structure affect economic growth in different ways at different stages of the demographic transition. For many countries of the world, the demographic bonus is relevant, as economic growth rates can increase when dependency ratios decline (Bloom and Williamson 1998; Bloom and Canning 2008; Bloom et al. 2007; Hawksworth and Cookson 2008: 7–10; Lee and Mason 2006, 2011; Barsukov 2019; Groth et al. 2019; Kotschy et al. 2020; Korotayev, Shulgin et al. 2022). The most developed countries, however, are facing a demographic onus due to population ageing (see Ogawa, Kondo, and Matsu-kura 2005; Komine and Kabe 2009; Park and Shin 2015; Goldstone 2015; Barsukov 2019; Hsu and Lo 2019; Warsito 2019; Grinin, Grinin, and Malkov 2023a; Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b; Grinin, Grinin, and Malkov 2023b).

Reverse effect:

– improvement in the material living conditions of the population (GDP per capita) due to economic growth affects the reduction in mortality and an increase in life expectancy, and vice versa. An economic slowdown in countries that have completed the demographic transition may contribute to a further decline in fertility.

2.5. The Impact of Demography on the Social Sphere

Population density and urbanization that are still growing globally require transformations of social institutions:

– the growing proportion of older people affects the value system of the society. ‘Global ageing’ often provokes negative connotations. However, according to some researches, with regard to value system, global ageing can also lead to some positive effects due to increased support for prosocial values (see Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b; Korotayev, Shulgin et al. 2018; Shulgin et al. 2019; Korotayev, Novikov et al. 2019; Mayr and Freund 2020; Korotayev, Butovskaya et al. 2021);

– migration can lead to social disproportions and differentiation.

Reverse effect:

– an increase in the level of education in most cases leads to a decrease in fertility, and is also correlated with a decrease in mortality (Singh and Casterline 1985; Soares 2005; Korotayev et al. 2006a; Kebede et al. 2019; Vollset et al. 2020);

– social stratification affects the differentiation of mortality rates;

– changes in values (e.g., the spread of the ‘childfree’ ideology) affect birth rates.

2.6. The Impact of Demographics on Politics

Population ageing can potentially reduce the intensity of violent destabilization processes due to disappearing youth bulges (e.g., Cincotta and Weber 2021):

– population ageing can lead to some increase in conservative and right-wing orientations in society, and provide greater support for conservative and right-wing political parties (see Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b; Van Hiel and Brebels 2011; Tilley and Evans 2014; Korotayev et al. 2018).

Reverse effect:

– the influence of politics on demographic processes is channeled primarily through changes in legislation and the implementation of state programs (targeted to support the birth rates, reduce mortality, regulate migration, etc.) (see Grinin, Grinin, and Malkov 2023b; Grinin, Malkov, and Korotayev 2023; Grinin and Korotayev 2023).

3.

Retrospective Analysis of Changes

in the Demographic Sphere in the Historical Perspective

(for the last 8,000 years)

World population growth accelerated significantly after the Neolithic revolution that allowed a tremendous increase in the anthropological carrying capacity of the Earth (e.g., Livi-Bacci 2017; Korotayev 2020a). Population growth occurred to a large extent due to an increase in birth rates and a smoothing out of the peaks of catastrophic mortality, while the overall mortality of early farmers was, as a rule, higher than that of hunter-gatherers. The general downward trend in life expectancy (LE) after the Neolithic Revolution reached its lowest level among intensive farmers (Cohen 1989, 1998, 2009; Cohen and Armelagos 1984; Storey 1985; Cohen and Crane-Kramer 2007; Ember et al. 2017; Algaze 2018; Fagan and Durrani 2018). But the trend towards population growth took place due to a certain increase in fertility after the Neolithic (Agrarian) Revolution, growth of the anthropological carrying capacity of the Earth and smoothing out of catastrophic fluctuations in mortality. A steady systematic increase in life expectancy began to be observed only as part of the demographic transition that began in the most developed countries in the early 19th century (Chesnais 1992; Reher 2011; Dyson 2010; Livi-Bacci 2017).

The demographic transition is a transition from the traditional type of reproduction, which is characterized by high mortality and high fertility, to its modern type, characterized by low mortality and low fertility. At the first phase of the transition there is a drastic decrease in mortality due to a radical change in the structure of causes of death; thus, there is a transition from traditional to modern type of mortality. In modern societies, improved food security, development of water supply and sewerage systems, dramatic progress of health care technologies and expansion of access to them for the wide masses of population, as well as the dissemination of modern medical knowledge achieved in the course of modernization, have made it possible to establish effective control over many types of mortality (Chesnais 1992; Caldwell et al. 2006; Dyson 2010). At the second stage of the demographic transition, changes affect fertility. In traditional societies ‘the objective goal [of demographic regulation], reflected in cultural norms ... has always been a high birth rate’ (Vishnevsky 2005: 111) that was necessary in conditions of high mortality in order to guarantee that the population would not die out. After a significant decrease in mortality, a decrease in birth rate becomes a necessary condition for maintaining demographic equilibrium. ‘Low fertility, ... which, in combination with low mortality, reliably ensures the continuity of the process of renewal of generations, is now turning into a means of achieving a more general demographic goal (simple or slightly expanded reproduction, and thereby the goal of birth control)’ (Vishnevsky 2005: 114). The current situation is described in Section 1 of this article.

4. Demographic Development Scenarios

As shown above, the most important feature of modern demographic dynamics is that in all regions of the world, except for Tropical Africa, a second demographic transition has proceeded quite far (or has already been completed), which is accompanied by a decrease in birth rates and a corresponding slowdown in population growth, or even population decline. The only uncertain parameter is the speed at which birth rates will decrease in the whole world (at the same time, the demographic situation will develop differently in different countries and regions). This uncertainty determines a set of probable demographic scenarios that were calculated on the basis of mathematical models, taking into account current trends and hypotheses about further dynamics of demographic processes:

– the upper scenario implies continued growth of the world population in the 21st century with the stabilization of its numbers in the 22nd century;

– the medium scenario implies stabilization of the world population by the end of the 21st century;

– the lower scenario implies stabilization of the world population with a subsequent decline in the second half of the 21st century.

The upper scenario is derived from the assumption of continued demographic divergence, implying that fertility in the most developed and moderately developed countries remains at its current low levels or even declines further. Another assumption is that birth rates in Tropical African countries cease to decline at values greater than required for population replacement, approximately at 2.3 children per woman, while birth rates of the Islamic countries of North Africa and the Middle East stop declining at a level just above simple replacement of generations (about 2.1 children per woman).

The medium scenario is based on the assumption of demographic convergence, which implies, on the one hand, that the countries that have not yet completed the demographic transition will see their fertility rates decline at the fastest possible speed to the level of simple replacement of generations. On the other hand, in the countries with ultra-low fertility, rates will increase and return to the level of simple replacement of generations. This scenario seems to be more favorable in comparison with the upper scenario, as it will contribute to smoothing the tension between the center and the periphery of the World System, optimization of migration flows, prevention of socio-demographic collapses in the least developed countries, etc. (for more details see Korotayev et al. 2023).

The lower scenario assumes a decrease in birth rates below the replacement level in all countries of the world without exception, which will cause global depopulation.

The calculations for these scenarios are shown in Fig. 21. These calculations correlated quite well with the UN projections presented in the recent issues of the World Population Prospects (UN Population Division 2019, 2022b).

Fig. 4. Possible scenarios for world demographic dynamics up to 2100, billion people (1 –upper scenario, 2 – middle scenario, 3 – lower scenario)

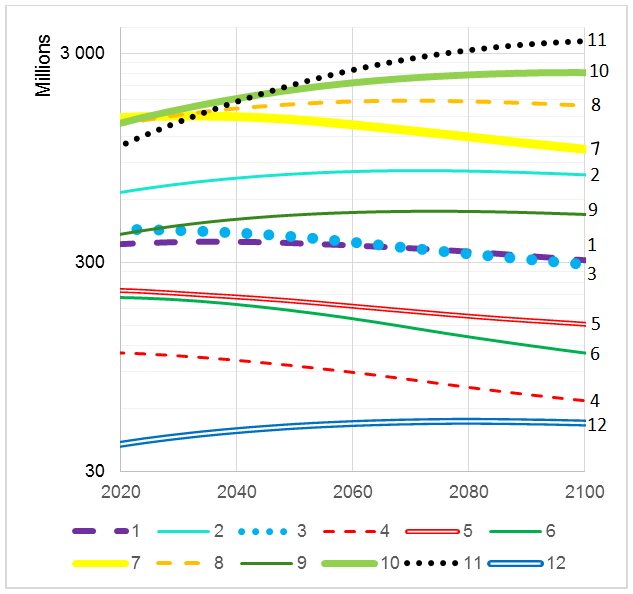

Calculations demonstrate the inevitability of a significant change of population numbers in different regions and civilizations, which will significantly affect world processes in the course of the 21st century (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Population dynamics in various regions of the world according to the medium scenario, millions, logarithmic scale (1 – North America, 2 – Latin America, 3 – Western Europe, 4 – Eastern Europe, 5 – Russia and CIS countries, 6 – Japan and Korea, 7 – China, 8 – India, 9 – Southeast Asia, 10 – Middle East and North Africa, 11 – Sub-Saharan Africa, 12 – Australia, New Zealand, Oceania)

We can see that, by the end of the 21st century, Tropical Africa will definitely come out on top in terms of population, overtaking both China and India. Moreover, in 2100, every second inhabitant of the Earth will be from Africa or the Middle East. These changes are typical for all scenarios and get more pronounced from the lower scenario to the upper one (see Table).

Table. Shares of population of the regions in the total population of the Earth

|

Region |

North

Ame- |

Latin

Ame- |

West- |

East- |

Russia

and |

Japan and South Korea |

China |

India |

South- |

Middle

East |

Sub-Saha- |

Aust- |

|

2020 |

4.76 % |

8.37 % |

5.62 % |

1.44 % |

2.87 % |

2.66 % |

19.15 % |

17.74 % |

5.27 % |

17.83 % |

13.72 % |

0.52 % |

|

2100 upper scenario |

2.49 % |

6.48 % |

2.26 % |

0.50 % |

1.15 % |

0.75 % |

6.76 % |

14.01 % |

4.22 % |

22.55 % |

38.43 % |

0.43 % |

|

2100 medium scenario |

2.83 % |

7.24 % |

2.70 % |

0.60 % |

1.40 % |

1.02 % |

9.61 % |

15.53 % |

4.68 % |

22.33 % |

31.58 % |

0.47 % |

|

2100 lower scenario |

3.29 % |

7.92 % |

3.24 % |

0.73 % |

1.59 % |

1.27 % |

11.33 % |

16.34 % |

4.97 % |

22.09 % |

26.75 % |

0.49 % |

We believe that the most favorable scenario for solving existing global problems is the medium demographic development scenario (the convergence scenario). Stabilization of the Earth's population will slow down the negative anthropogenic impact on the natural environment and ensure a systematic reduction of this pressure.

According to IHME calculations (Vollset et al. 2020), in order to achieve a favorable demographic development scenario for the most demographically lagging countries (i.e., to complete the demographic transition as quickly as possible), it would be sufficient to achieve sustainable development goals in the field of education (especially women's education) and access to family planning, which seems extremely plausible (see Soares 2005; Zinkina and Korotayev 2014a; Kebede et al. 2019; Korotayev et al. 2023). For developed countries to enter the convergence scenario, a rise in birth rates is necessary, which can be achieved, first of all, through family policy measures. Research shows that the most effective way to increase fertility in the countries with dangerously low birth rates is to provide a combination of cash and tax benefits for families with children, as well as government programs and laws to support women who combine work and raising children (access to kindergarten services, babysitting, flexible working hours for mothers, etc.) (see, e.g., Arkhangelsky et al. 2015).

References

Akaev A., and Davydova O. 2023. Climate and Energy. Energy Transition Scenarios and Global Temperature Changes Based on Current Technologies and Trends. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 53–70. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_4

Algaze G. 2018. Entropic Cities: The Paradox of Urbanism in Ancient Mesopotamia. Current anthropology 59(1): 23–54. https://doi.org/10.1086/695983

Arkhangelsky V., Bogevolnov J., Goldstone J., Khaltourina D., Korotayev A., Malkov A., et al. 2015. Critical 10 Years. Demographic Policies of the Russian Federation: Successes and Challenges. Moscow: Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA).

Barsukov V. N. 2019. From the Demographic Dividend to Population Ageing: World Trends in the System-Wide Transition. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast 12(4): 167–182. https://doi.org/10.15838/esc.2019.4.64.11

Bengtson V. (Ed.) 2018. Global Ageing and Challenges to Families. Routledge.

Bloom D. E., and Canning D. 2008. Global Demographic Change: Dimensions and Economic Significance. Population and Development Review 34: 17–51.

Bloom D. E., and Williamson J. G. 1998. Demographic Transitions and Economic Miracles in Emerging Asia. World Bank Economic Review 12(3): 419–455.

Bloom D. E., Canning D., Fink G., and Finlay J. 2007. Does Age Structure Forecast Economic Growth? International Journal of Forecasting 23(4): 569–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2007.07.001

Boserup E. 1965. The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure. Aldine.

Caldwell J. C., Caldwell B. K., Caldwell P., McDonald P. F., and Schindlmayr T. 2006. Demographic Transition Theory. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4498-4

Chesnais J. C. 1992. The Demographic Transition: Stages, Patterns, and Economic Implications. Clarendon Press.

Cincotta R., and Weber H. 2021. Youthful Age Structures and the Risks of Revolutionary and Separatist Conflicts. Global Political Demography: Comparative Analyzes of the Politics of Population Change in All World Regions / Ed. by A. Goerres, and P. Vanhuysse, pp. 57–92. Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73065-9_3

Cohen M. N. 1989. Health and the Rise of Civilization. Yale University Press.

Cohen M. N. 1998. Were Early Agriculturalists Less Healthy Than Food Collectors? Research Frontiers in Anthropology / Ed. by C. R. Ember, M. Ember, and P. N. Peregrine, pp. 61–83. Prentice Hall.

Cohen M. N. 2009. Introduction: Rethinking the Origins of Agriculture. Current Anthropology 50(5): 591–595. https://doi.org/10.1086/603548

Cohen M. N., and Armelagos G. J. (Eds.) 1984. Paleopathology at the Origins of Agriculture. Academic Press.

Cohen M. N., and Crane‐Kramer G. (Eds.) (2007). Bioarchaeological Interpretations of the Human Past: Local, Regional, and Global Perspectives Series. University Press of Florida.

Dyson T. 2010. Population and Development. The Demographic Transition. Zed Books.

Ember C. R., Ember M., Peregrine P. N., Hoppa R. D., and Fowler K. 2017. Physical Anthropology and Archaeology. Pearson.

Fagan B. M., and Durrani N. 2018. People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory. Routledge.

Fichtner J. J. 2018. Global Ageing and Public Finance. Business Economics 53(2): 72–78.

Foerster H., von Mora P. M., and Amiot L. W. 1960. Doomsday: Friday, 13 November, A.D. 2026: At This Date Human Population Will Approach Infinity If It Grows As It Has Grown in the Last Two Millennia. Science 132(3436): 1291–1295. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.132.3436.1291

Goldstone J. A. 2015. Population Ageing and Global Economic Growth. History & Mathematics: Political Demography & Global Ageing / Ed. by J. A. Goldstone, L. Grinin, and A. Korotayev, pp. 147–155. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Goldstone J. A., Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2015. Research into Global Ageing and Its Consequences. History & Mathematics: Political Demography & Global Ageing / Ed. by J. A. Goldstone, L. Grinin, and A. Korotayev, pp. 5–9. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Grinin L., and Grinin A. 2023. Technologies. Limitless Possibilities and Effective Control. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 139–154. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_8

Grinin L. E., Grinin A. L., and Korotayev A. 2017. Forthcoming Kondratieff wave, Cybernetic Revolution, and Global Ageing. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 115: 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.09.017

Grinin L., Grinin A., and Korotayev A. 2020. Dynamics of Technological Growth Rate and the Forthcoming Singularity. The 21st Century Singularity and Global Futures. A Big History Perspective / Ed. by A. Korotayev, and D. LePoire, pp. 287–344. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33730-8_14

Grinin L., Grinin A., and Korotayev A. 2022. COVID-19 Pandemic as a Trigger for the Acceleration of the Cybernetic Revolution, Transition From E-Government to E-State, and Change in Social Relations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 175: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121348

Grinin L., Grinin A., and Korotayev A. 2023a. Future Political Change. Toward a More Efficient World Order. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 191–206. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_11

Grinin L., Grinin A., and Korotayev A. 2023b. Global Ageing – an Integral Problem of the Future. How to Turn a Problem into a Development Driver? Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 117–135. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_7

Grinin L., Grinin A., and Malkov S. 2023a. Economics: Optimizing Growth. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 155–168. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_9

Grinin L., Grinin A., and Malkov S. 2023b. Socio-Political Transformations. A Difficult Path to Cybernetic Society. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 169–190. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_10

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2015. Great Divergence and Great Convergence. A Global Perspective. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17780-9

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2023. Africa: The Continent of the Future. Challenges and Opportunities. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 225–240. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_13

Grinin L., Malkov S., and Korotayev A. 2023. High Income and Low-Income Countries. Towards a Common Goal at Different Speeds. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 207–224. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_12

Groth H., May J. F., and Turbat V. 2019. Policies Needed to Capture a Demographic Dividend in Sub-Saharan Africa. Canadian Studies in Population 46(1): 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42650-019-00005-8

Hawksworth J., and Cookson G. 2008. The World in 2050. Beyond the BRICs: A Broader Look at Emerging Market Growth Prospects. PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Hsu Y. H., and Lo H. C. 2019. The Impacts of Population Ageing on Saving, Capital Formation, and Economic Growth. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management 9(12): 2231–2246. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2019.912148

Kapitza S. 2006. Global Population Blow-Up and After. Report to the Club of Rome. Global Marshall Plan Initiative.

Kebede E., Goujon A., and Lutz W. 2019. Stalls in Africa's Decline Partly Result from Disruptions in Female Education. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(8): 2891–2896. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1717288116

Komine T., and Kabe S. 2009. Long‐Term Forecast of the Demographic Transition in Japan and Asia. Asian Economic Policy Review 4(1): 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3131.2009.01103.x

Korotayev A. 2005. A Compact Macromodel of World System Evolution. Journal of World-Systems Research 11(1): 79–93. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2005.401

Korotayev A. 2007. Compact Mathematical Models of World System Development, and How They Can Help Us to Clarify Our Understanding of Globalization Processes. Globalization as Evolutionary Process: Modeling Global Change / Ed. by G. Mo-delski, T. Devezas, and W. Thompson, pp. 133–160. Routledge.

Korotayev A. 2020a. How Singular Is the 21st Century Singularity? The 21st Century Singularity and Global Futures. A Big History Perspective / Ed. by A. Korotayev, and D. LePoire, pp. 571–595. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33730-8_26

Korotayev A. 2020b. The 21st Century Singularity in the Big History Perspective. A Re-Analysis. The 21st Century Singularity and Global Futures. A Big History Perspective / Ed. by A. Korotayev, and D. LePoire, pp. 19–75. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33730-8_2

Korotayev A., Butovskaya M., Shulgin S., and Zinkina J. 2021. Impact of Population Ageing on the Global Value System. Vek Globalizatsii 4: 69–80. https://doi.org/10.30884/vglob/2021.04.05

Korotayev A., Goldstone J., and Zinkina J. 2015. Phases of Global Demographic Transition Correlate with Phases of the Great Divergence and Great Convergence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 95: 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.01.017

Korotayev A., and Malkov A. 2016. A Compact Mathematical Model of the World System Economic and Demographic Growth, 1 CE – 1973 CE. International Journal of Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 10: 200–209.

Korotayev A., Malkov A., and Khaltourina D. 2006a. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Compact Macromodels of the World System Growth. KomKniga/URSS.

Korotayev A., Malkov A., and Khaltourina D. 2006b. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Secular Cycles and Millennial Trends. KomKniga/URSS.

Korotayev A., Novikov K., and Shulgin S. 2019. Values of the Elderly People in an Ageing World. Sociology of Power 31(1): 114–142. https://doi.org/10.22394/2074-0492-2019-1-114-142

Korotayev A., Shulgin S., Ustyuzhanin V., Zinkina J., and Grinin L. 2023. Modeling Social Self-Organization and Historical Dynamics. Africa's Futures. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 461–490. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_20

Korotayev A., Shulgin S., Zinkina J., and Novikov K. 2018. The Impact of Population Ageing on the Global Value System and Political Dynamics. Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration.

Korotayev A., Shulgin S., Zinkina J., and Slav M. 2022. Estimates of the Possible Economic Effect of the Demographic Dividend for Sub-Saharan Africa for the Period up to 2036. Vostok (Oriens) (2): 108–123. https://doi.org/10.31857/S086919080019128-7

Korotayev A., and Zinkina J. 2014.

How to Optimize Fertility and Prevent Humanitarian Catastrophes in Tropical

Africa. African Studies in Russia 6: 94–107.

https://

elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=22501708

Korotayev A., and Zinkina J. 2015. East Africa in the Malthusian Trap? Journal of Developing Societies 31(3): 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0169796X15590322

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., Goldstone J., and Shulgin S. 2016. Explaining Current Fertility Dynamics in Tropical Africa from an Anthropological Perspective: A Cross-Cultural Investigation. Cross-Cultural Research 50(3): 251–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397116644158

Kotschy R., Urtaza P. S., and Sunde U. 2020. The Demographic Dividend Is More Than an Education Dividend. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(42): 25982–25984. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.201228611

Kovaleva N. 2023. Ecology: Life in the ‘Unstable Biosphere’. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 71–96. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_2

Kremer M. 1993. Population Growth and Technological Change: One Million B.C. to 1990. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 108: 681–716. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118405

Lee R., and Mason A. 2006. What is the Demographic Dividend? Finance and Development 43(3): 16–17.

Lee R., and Mason A. 2011. Population Ageing and the Generational Economy: A Global Perspective. Edward Elgar.

Lesthaeghe R. 2020. The Second Demographic Transition, 1986–2020: Sub-Rep-lacement Fertility and Rising Cohabitation – A Global Update. Genus 76(1): 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-020-00077-4

Livi-Bacci M. 2017. A Concise History of World Population. Wiley-Blackwell.

Lutz W., Goujon A., Kc S., Stonawski M., and Stilianakis N. 2018. Demographic and Human Capital Scenarios for the 21st Century: 2018 Assessment for 201 Countries. Publications Office of the European Union.

Maddison Project. 2020. Maddison Project Database 2020. Groningen Growth and Development Centre. URL: https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2020.

May J. F., and Rotenberg S. 2020. A Call for Better Integrated Policies to Accelerate the Fertility Decline in Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning 51(2): 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12118

Mayr U., and Freund A. M. 2020. Do We Become More Prosocial as We Age, and If So, Why? Current Directions in Psychological Science 29(3): 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420910811

Meadows D. H., Meadows D. L., Randers J., and Behrens W. W. 1972. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind. Universe Books.

Mitchell E., and Walker R. 2020. Global Ageing: Successes, Challenges and Opportunities. British Journal of Hospital Medicine 81(2): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2019.0377

Nath S. K. 2020. Demographic Transition and Economic Growth. Solid State Technology 63(5): 3142–3148.

Nzimande N., and Mugwendere T. 2018. Stalls in Zimbabwe Fertility: Exploring Determinants of Recent Fertility Transition. Southern African Journal of Demography 18(1): 59–110.

Ogawa N., Kondo M., and Matsukura R. 2005. Japan's Transition from the Demographic Bonus to the Demographic Onus. Asian Population Studies 1(2): 207–226.

Park D., and Shin K. 2015.

Impact of Population Ageing on Asia's Future Growth. History & Mathematics: Political Demography & Global Ageing / Ed. by J. A. Gold-

stone, L. Grinin, and A. Korotayev, pp. 107–132. Volgograd:

Uchitel.

Podlazov A. 2017. A Theory of the Global Demographic Process. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences 87(3): 256–266. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1019331617030054

Reher D. 2011. Economic and Social Implications of the Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review 37: 11–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00376.x

Schoumaker B. 2019. Stalls in Fertility Transitions in Sub-Saharan Africa: Revisiting the Evidence. Studies in Family Planning 50(3): 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12098

Shulgin S., Zinkina J., and Korotayev A. 2019. Religiosity and Ageing: Age and Cohort Effects and Their Implications for the Future of Religious Values in High‐Income OECD Countries. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58(3): 591–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12613

Singh S., and Casterline J. 1985. The Socio-Economic Determinants of Fertility. Reproductive Change in Developing Countries. Insights from World Fertility Survey / Ed. by J. Cleland, and J. Hobcraft, pp. 199–222. Oxford University Press.

Soares R. 2005. Mortality Reductions, Educational Attainment, and Fertility Choice. American Economic Review 95(3): 580–601. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828054201486

Storey R. 1985. An Estimate of Mortality in a Pre-Columbian Urban Population. American Anthropologist 87: 515–535.

Taagepera R. 1976. Crisis around 2005 AD? A Technology-Population Interaction Model. General Systems 21: 137–138.

Taagepera R. 1979. People, Skills, and Resources: An Interaction Model for World Population Growth. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 13: 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1625(79)90003-9

Tilley J., and Evans G. 2014. Ageing and Generational Effects on Vote Choice: Combining Cross-Sectional and Panel Data to Estimate APC Effects. Electoral Studies 33: 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2013.06.007

Tsirel S. 2004. On the Possible Reasons for the Hyperexponential Growth of the Earth Population. Mathematical Modeling of Social and Economic Dynamics / Ed. by M. G. Dmitriev, and A. P. Petrov, pp. 367–369. Russian State Social University.

UN Population Division. 2018. World Urbanization Prospects 2018. United Nations.

UN Population Division. 2019. World Population Prospects 2019. United Nations.

UN Population Division. 2022a. United Nations Population Division Database. United Nations. URL: http://www.un.org/esa/population.

UN Population Division. 2022b. World Population Prospects 2022. United Nations.

Van Hiel A., and Brebels L. 2011. Conservatism Is Good for You: Cultural Conservatism Protects Self-Esteem in Older Adults. Personality and Individual Differences 50(1): 120–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.002

Vishnevsky A. 2005. Selected Demographic Works. Vol. 1. Demographic Theory and Demographic History. Moscow: Nauka. In Russian (Вишневский А. Избранные демографические труды. Т. 1. Демографическая теория и демографическая история. М.: Наука).

Vollset S. E., Goren E., Yuan C.-W., Cao J., Smith A. E., Hsiao T. et al. 2020. Fertility, Mortality, Migration, and Population Scenarios for 195 Countries and Territories From 2017 to 2100: A Forecasting Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet 396(10258): 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30677-2

Wallerstein I. 1987. World-Systems Analysis. Social Theory Today / Ed. by A. Giddens, and J. H. Turner, pp. 309–324. Cambridge University Press.

Warsito T. 2019. Attaining the Demographic Bonus in Indonesia. Jurnal Pajak Dan Keuangan Negara (PKN) 1(1): 6–16.

Zimmer Z. 2016. Global Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: Challenges, Opportunities and Implications. Routledge.

Zinkina J., and Korotayev A. 2014a. Explosive Population Growth in Tropical Africa: Crucial Omission in Development Forecasts (Emerging Risks and Way Out). World Futures 70(4): 271–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2014.894868

Zinkina J., and Korotayev A. 2014b. Projecting Mozambique's Demographic Futures. Journal of Futures Studies 19(2): 21–40.

* This research has been implemented with the support of the Russian Science Foundation (Project № 23-11-00160).

[1] For a discussion of demographic problems in Tropical Africa see Zinkina and Korotayev 2014a; Korotayev, Zinkina et al. 2016; Nzimande and Mugwendere 2018; Schoumaker 2019; May and Rotenberg 2020; Grinin and Korotayev 2023; Korotayev et al. 2023. In addition, see Grinin, Malkov, and Korotayev 2023.