The Nineteenth-Century Urbanization Transition in the First World

Almanac: Globalistics and Globalization Studies Global Evolution, Historical Globalistics and Globalization Studies

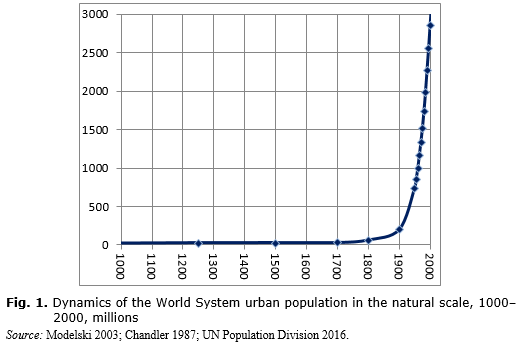

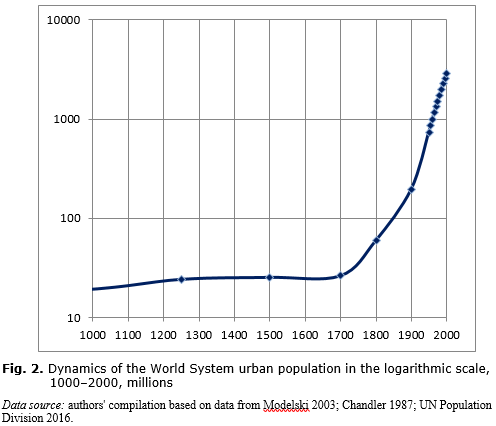

The paper focuses on the period of increasing and intensified growth of urbani-zation in the nineteenth century. That was the origin of the modern urbanized world. The authors emphasize, however, that in the nineteenth century urbanization was initially vibrant in Europe and the USA. In other world regions rapid urbanization started mostly in the twentieth century and led to a tremendous increase of the world urban population from less than 200 million in 1900 to 2.86 billion in 2000.

Keywords: urbanization, cities, Europe, the nineteenth century.

To start with, let us consider the dynamics of urbanization in the nineteenth century in a broader, millennial perspective (see Fig. 1).

In other regions of the world the situation was pretty much the same, with urbanization levels being approximately the same as or even lower than in Europe. In China with its rich history of urban culture only 6–7.5 per cent of the population resided in cities (population exceeding 5,000 people) in the early nineteenth century (Bairoch 1988: 358). In Japan about 11–14 per cent of population dwelled in cities in 1700 (Ibid.: 360).

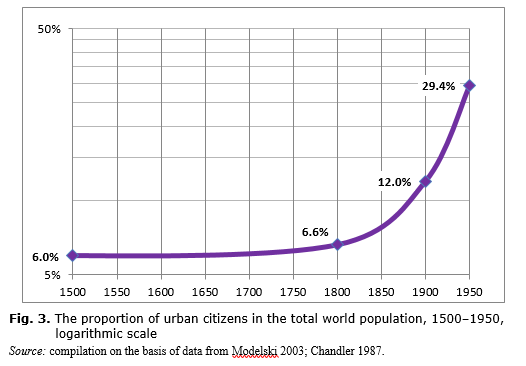

The nineteenth century broke this long-term stability, as the share of world urban population doubled from 6.6 per cent in 1800 to 12 per cent in 1900. The growth of urban population significantly outpaced the growth of the world population in general. This allows us to state that it was namely in the nineteenth century that the modern process of global urbanization began.

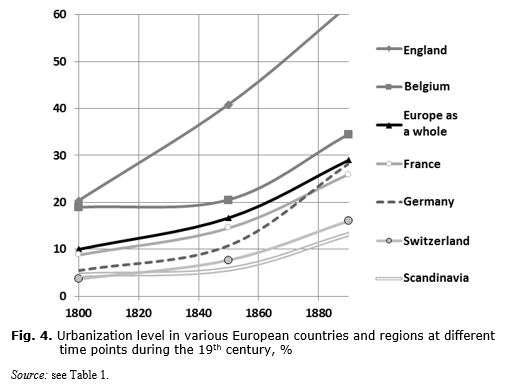

However, despite its crucial influence on various spheres of life, the pace of the urban population growth in the nineteenth century should not be exaggerated. It was particularly fast in Western Europe, but even here only one country, Great Britain, was more or less close to completing the urban transition by the end of the nineteenth century – more than half of its population resided in cities by 1900. Meanwhile, other European countries had only passed the initial stages of the urbanization process; even the leaders, such as Belgium and the Netherlands, had only about one-third of their population dwelling in cities by 1890 (see Table 1 and Fig. 4).

Table 1. The share of urban population in various European countries and regions at different time points during the 19th century, %

|

Country/region |

1800 |

1850 |

1890 |

|

England |

20.3 |

40.8 |

61.9 |

|

Belgium |

18.9 |

20.5 |

34.5 |

|

Germany |

5.5 |

10.8 |

28.2 |

|

France |

8.8 |

14.5 |

25.9 |

|

Spain |

11.1 |

17.3 |

26.8 |

|

Italy |

14.6 |

20.3 |

21.2 |

|

The Netherlands |

28.8 |

29.5 |

33.4 |

|

Portugal |

8.7 |

13.2 |

12.7 |

|

Scandinavia |

4.6 |

5.8 |

13.2 |

|

Switzerland |

3.7 |

7.7 |

16.0 |

|

Total Europe |

10 |

16.7 |

29.0 |

Source: de Vries 1984: 45–46.

This growth was concentrated in large cities and especially the capitals. ‘The advantage of size meant growing economic opportunity in the metropolis, especially if it was also the seat of government, where the concentration of labor, entrepreneurship, commerce, credit, and intelligence attracted the restless and ambitious from all classes of society’ (Hamerow 1989: 94–95). However, not infrequently the capitals were outpaced by centers of industry and trade in attracting new citizens.

In the nineteenth century, large cities were growing all over the world. However, it was in Europe and in the USA that this growth was particularly pronounced (see Table 2). As a result of this, Europe and the USA greatly outpaced other world regions in terms of urbanization, and we see a major reconfiguration of the global distribution of the world largest cities. This phenomenon is clearly visible when comparing the list of 30 largest cities of the world in 1800 with that in 1914 (see Table 3).

Table 2. Absolute (thousands) and relative (%) population growth in 1800–1914 in 30 largest (as of 1914) cities of the world

|

|

City |

Absolute population growth during the |

Relative population growth during the 19th century, % (population in 1800 = 100 %) |

|

1. |

London |

6,558 |

762 |

|

2. |

New York |

6,637 |

10,535 |

|

3. |

Paris |

3,453 |

631 |

|

4. |

Berlin |

3,328 |

1,935 |

|

5. |

Tokyo |

2,815 |

411 |

|

6. |

Chicago |

2,420 |

Established after 1800 |

|

7. |

Vienna |

1,918 |

830 |

|

8. |

Saint-Petersburg |

1,913 |

870 |

|

9. |

Moscow |

1,557 |

628 |

|

10. |

Philadelphia |

1,692 |

2,488 |

|

11. |

Buenos Aires |

1,596 |

4,694 |

|

12. |

Manchester |

1,519 |

1,875 |

|

13. |

Birmingham |

1,429 |

2,013 |

|

14. |

Osaka |

1,097 |

286 |

|

15. |

Calcutta |

1,238 |

764 |

|

16. |

Boston |

1,269 |

3,626 |

|

17. |

Liverpool |

1,224 |

1,611 |

|

18. |

Hamburg |

1,183 |

1,011 |

|

19. |

Glasgow |

1,041 |

1,239 |

|

20. |

Constantinople |

555 |

97 |

|

21. |

Rio de Janeiro |

1,046 |

2,377 |

|

22. |

Bombay |

940 |

671 |

|

23. |

Budapest |

996 |

1844 |

|

24. |

Beijing |

–100 |

–9 |

|

25. |

Shanghai |

910 |

1011 |

|

|

City |

Absolute population growth during the |

Relative population growth during the 19th century, % (population in 1800 = 100 %) |

|

26. |

Warsaw |

831 |

1108 |

|

27. |

St. Louis |

804 |

2 |

|

28. |

Tianjin |

655 |

504 |

|

29. |

Pittsburgh |

774 |

51567 |

|

30. |

Cairo |

649 |

295 |

Source: Chandler 1987.

Table 3. 30 largest cities of the world in 1800 and in 1914 (cities of Europe and the USA are printed in bold type)

|

1800 |

1914 |

||||

|

City |

Country |

Population in 1800, thousands |

City |

Country |

Population in 1914, thousands |

|

Beijing |

China |

1,100 |

London |

Great Britain |

7,419 |

|

London |

Great Britain |

861 |

New York |

the USA |

6,700 |

|

Canton |

China |

800 |

Paris |

France |

4,000 |

|

Edo |

Japan |

685 |

Berlin |

Germany |

3,500 |

|

Constantinople |

the Ottoman Empire |

570 |

Tokyo |

Japan |

3,500 |

|

Paris |

France |

547 |

Chicago |

the USA |

2,420 |

|

Naples |

Kingdom of Naples |

430 |

Vienna |

Austria |

2,149 |

|

Hangzhou |

China |

387 |

Saint-Petersburg |

Russia |

2,133 |

|

Osaka |

Japan |

383 |

Moscow |

Russia |

1,805 |

|

Kyoto |

Japan |

377 |

Philadelphia |

the USA |

1,760 |

|

Moscow |

Russia |

248 |

Buenos Aires |

Argentina |

1,630 |

|

Suzhou |

China |

243 |

Manchester |

Great Britain |

1,600 |

|

Lucknow |

India (Great Britain) |

240 |

Birmingham |

Great Britain |

1,500 |

|

Lisbon |

Portugal |

237 |

Osaka |

Japan |

1,480 |

|

Vienna |

Austria |

231 |

Calcutta |

India |

1,400 |

|

Xian |

China |

224 |

Boston |

the USA |

1,304 |

|

Saint-Petersburg |

Russia |

220 |

Liverpool |

Great Britain |

1,300 |

|

Amsterdam |

Netherlands |

195 |

Hamburg |

Germany |

1,300 |

|

Seoul |

Korea |

194 |

Glasgow |

Great Britain |

1,125 |

|

Murshidabad |

India (Great Britain) |

190 |

Constantinople |

the Ottoman Empire |

1,125 |

|

Cairo |

Egypt |

186 |

Rio de Janeiro |

Brazil |

1,090 |

|

Madrid |

Spain |

182 |

Bombay |

India |

1,080 |

|

Benares |

India (Great Britain) |

179 |

Budapest |

Hungary |

1,050 |

|

Amarapura |

Burma |

175 |

Beijing |

China |

1,000 |

|

Hyderabad |

India (Great Britain) |

175 |

Shanghai |

China |

1,000 |

|

Berlin |

Germany |

172 |

Warsaw |

Poland |

906 |

|

Patna |

India (Great Britain) |

170 |

St. Louis |

the USA |

804 |

|

Dublin |

Ireland |

165 |

Tianjin |

China |

785 |

|

Kintechen |

China |

164 |

Pittsburgh |

the USA |

775 |

|

Calcutta |

India (Great Britain) |

162 |

Cairo |

Egypt |

735 |

Source: Chandler 1987.

While in 1800 only three out of the world's ten largest cities were located in Europe, in 1914 nine out of ten largest cities belonged to the European region or the USA. The only exception, Tokyo, supports the general rule, as Japan was the most successful example of the European-style modernization outside the European world.

The dynamics of the total population of the 30 largest cities of the world between 1800 and 1914 was explosion-like (see Fig. 5). Data on the population growth in the seven largest cities of the world in 1800–1914 are presented in Fig. 6.

The Emergence of Modern-Type Cities

Sanitary infrastructure. For much of the nineteenth century the death rates in urban areas remained extremely high, especially considering infant and child mortality. For example, in British industrial cities of Lancashire and Cheshire 198 out of 1,000 children died before their first birthday – twice more than in rural areas (Bairoch 1988: 67). In the French city of Lille, one-quarter of children died before the age of three years (Lees and Lees 2007: 143). A similar situation had been observed in many other industrial cities in Europe. The main reasons for high mortality were dirty and unsanitary conditions in the streets and houses (especially in the poor working-class neighborhoods), and even the contamination of the air of industrial cities was unbearable (Schultz 1989: 112). Gradually, in the second half of the nineteenth century, various solutions were offered to the problems of urban sanitation infrastructure. Thus, private wells by central public water supply. By the end of the nineteenth century more than 40 of the 50 largest US cities had extensive water systems created and maintained by the state (Schultz 1989: 164). Previous ways of waste disposal (part of it was taken by farmers for fertilizing, but a significant portion was disposed of in a completely unsanitary manner – e.g., dumped and poured in the outskirts of the city) were overtaken by modern sewerage systems. These two phenomena (along with street paving, improvement of public lighting, etc.) played a crucial role in the development of cities and the decline of urban mortality.

Public transportation. Cities with hundreds of thousands citizens were confronted with the problem of organizing a transport network. Indeed, in contrast to the medieval craftsmen, industrial workers lived and worked in different places, so most of them had to commute every day. According to Paul Bairoch, the public transport system was born in 1828 in Paris (which then counted more than 800,000 people) when the city installed its first omnibus line. From Paris the public transport system spread throughout the Western world. Already in 1829, inspired by the success of Paris, London followed its example, and in 1831 New York did the same. In the next two decades the public transport system appeared in almost all the major cities in Europe and North America. Public transport rapidly gained popularity. By the end of the 1850s omnibuses in London and Paris carried 40 million passengers annually (Bairoch 1988: 281; Clark 2009: 273). In the 1850s the rail urban transport began to actively expand. The first electric tram was demonstrated by Siemens in 1879 and started working in Frankfurt in 1881. Electrification contributed to the development of the underground urban transport – on the eve of the First World War metro lines were functioning in 12 cities of the world, such as London (since 1863), New York (1868), Istanbul (1875), Budapest (1897), Glasgow (1897), Vienna (1898), Paris (1900), Boston (1901), Berlin (1902), Philadelphia (1907) Hamburg (1912), Buenos Aires (1913) (Bairoch 1988: 282).

Urban infrastructure. An important novelty of the nineteenth century was the idea of planning the urban landscape. The initiative belonged to Prussia where in 1808 each municipality was obliged to establish a building committee, responsible for street paving and drainage systems, as well as for the condition of sidewalks (Lees and Lees 2007: 123).

An integral part of the modern cities was constituted by numerous shops, especially large department stores, many of which (Le Bon Marché, the first department store, which opened in Paris in 1852, London's Selfridge, etc.) continue to operate today. Almost every major Western European city (as well as many small towns) for a certain period of the nineteenth century experienced a real boom in the opening of stores. For example, in Britain their number grew by 300 per cent in the first half of the nineteenth century. In Vienna the number of stores tripled in 1870–1902, while in Paris it increased eightfold (Clark 2009: 266).

Significant changes were taking place not only in the public space of cities, but also in private homes. By the middle of the nineteenth century rich American and European homes had running water; later this innovation appeared in the houses of the middle class. 93 percent of London houses had running water on the eve of the First World War (Clark 2009: 272). A change in house planning implied a separate room for hygiene procedures, which undoubtedly contributed to the decline in mortality from infectious diseases (Schultz 1989: 164).

References

Bairoch, P. 1988. Cities and Economic Development. From the Dawn of History to the Present. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Chandler, T. 1987. Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press.

Clark, P. 2009. European Cities and Towns: 400–2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hamerow, T. D. 1989. The Birth of a New Europe. State and Society in the Nineteenth Century. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press.

Lees, A., and Lees, L. H. 2007. Cities and the Making of Modern Europe, 1750–1914. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Modelski, G. 2003. World Cities: –3000 to 2000. Washington: FAROS 2000.

Schultz, S. K. 1989. Constructing Urban Culture: American Cities and City Planning, 1800 – 1920. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

UN Population Division. 2016. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division Database. URL: http://www.un.org/esa/population.

Vries, J., de. 1984. European Urbanization 1500–1800. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

* This research has been supported by Russian Science Foundation (project No 15-18-30063).