Africa's Dynamics: History and Possible Futures

Almanac: History & Mathematics:Political, Demographic, and Environmental Dimensions

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/978-5-7057-6354-2_03

Abstract

This article presents forecasts for the emergence of large-scale political and demographic collapses and for the economic growth of some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where the likelihood of armed civil conflicts and population impoverishment is the highest in the coming decades. The authors apply several advanced mathematical models: (1) to forecast the risks of armed conflict, where population, median age, and education are the main explanatory factors; and (2) to forecast economic growth, which is a function of the same variables and risks of large-scale armed civil conflicts. It is important to note that mathematical models consider the interaction of explanatory factors with each other, thereby creating feedback effects. Using these methods, the authors calculate three possible development scenarios for each of the countries under consideration in the 21st century: (1) a pessimistic one, (2) an inertial one and (3) an optimistic one assuming the achievement of sustainable development goals (SDGs) by 2030. The modeling results suggest that the Sahel could become the most disadvantaged region. The four countries of this region are characterized by: (1) a negligible difference between the inertial scenario and the pessimistic scenario; (2) extremely high risks of full-scale civil wars in the close future; and (3) reaching the level of middle-income countries only by the end of this century, even under the most optimistic scenario. The authors conclude that the main way of mitigating the risks of sociodemographic collapses is rapid progress towards achieving the SDGs in the very near future, which seems impossible without an adequate support of the world community.

Keywords: Sub-Saharan Africa, mathematical modeling, socio-demographic future, development scenario.

1. Modeling the Socio-Demographic Futures of Africa

1.1. An Overview

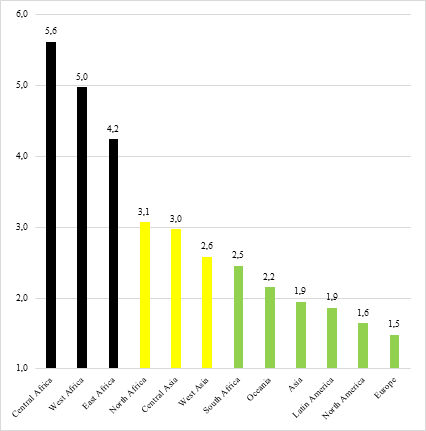

Currently, Tropical Africa is still characterized by very high fertility rates, which distinguish it fr om all the other regions of the world (see Fig. 1, see also Zinkina and Korotayev 2014a, 2014b; Korotayev et al. 2016; Nzimande and Mugwendere 2018; Kebede et al. 2019; Schoumaker 2019; May and Rotenberg 2020).

Fig. 1. Total fertility rates in various regions of the world in 2021

Source: UN Population Division Database 2022.

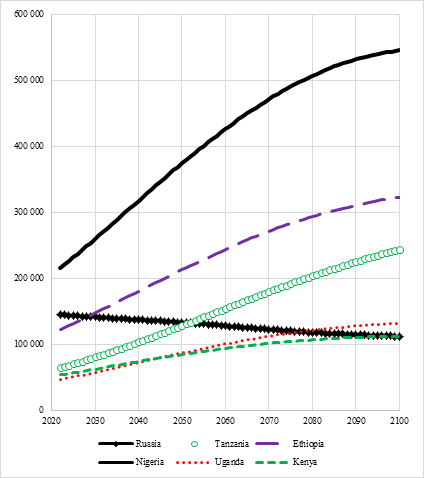

Given the very slow decline in fertility rates against the background of rather remarkable decline in mortality rates, it is hardly surprising that even the medium UN population forecasts imply impressive population growth in this region. For example, according to medium UN forecasts, the population of Kenya will catch up with the population of Russia by the end of this century, and the population of Uganda will even surpass it (see Fig. 2). The population of Tanzania will exceed the population of Russia by the mid-21st century, and Ethiopia's population will do this already by the 2030s; by the late 21st century, Tanzania and Ethiopia are projected to overtake Russia in terms of population size by almost two and three times, respectively.

Fig. 2. Population projections for some African countries in comparison with Russia, UN forecasts from 2020 to 2100 (thousands)

Source: UN Population Division Database 2022.

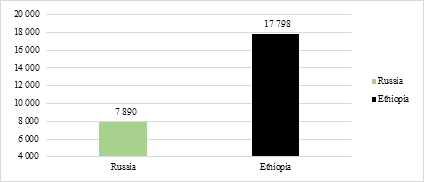

The easiest way to compare the expected populations of two countries is to compare the sizes of child age groups within the structures of their current populations. Thus, Ethiopia can be expected to overtake Russia in terms of population size very soon, as the number of children under five years old in Russia is currently less than eight million, while Ethiopia has nearly 18 million of children under five (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The number of children under five in Russia and Ethiopia in 2021 (thousands)

Source: UN Population Division Database 2022.

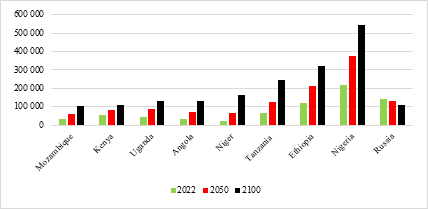

The largest increase in population is forecasted for Nigeria; by 2100 it

is projected to overtake the whole of Europe (including Russia), its population

is rocketing to reach more than 540 million people (see Fig. 4). Fig. 4

presents the population projections for Sub-Saharan countries with the largest

expected population increase in absolute terms that can result in catastrophic

consequences for the development of these countries. Projections of the

population of Russia are presented for the sake of comparison.

Fig. 4. Population projections for Sub-Saharan countries with the largest expected population increase in absolute terms and population projections for Russia

Source: UN Population Division Database 2022.

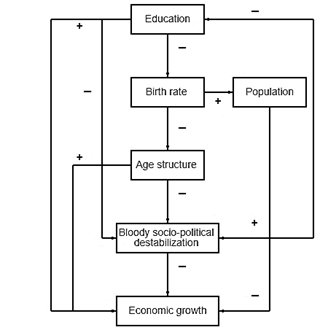

Below we will consider several scenarios of the socio-demographic development of the countries of Tropical Africa, corresponding to different scenarios for modernization processes in this part of our planet. A mathematical model with the following cognitive scheme is used to simulate the demographic future of African countries (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Cognitive scheme of the influence of various factors on economic growth and their interaction with each other

The expansion of formal education in the low-income and middle-income countries leads to a significant decrease in the birth rate (see, e.g., Zinkina and Ko-rotayev 2017; Kebede et al. 2019). In turn, fertility decline leads to an increase in the share of the working-age groups in the total population, creating the effect of the so-called ‘demographic bonus’ (see, e.g., Bloom et al. 2003; Bloom and Williamson 1998; Bloom et al. 2000; Omoruyi 2021; Korotayev, Shulgin et al. 2022). Fertility decrease brings down the youth bulges and leads to population aging (an increase in the median age), which, in turn, leads to a decrease in the risks of armed socio-political destabilization.[1] The spread of education reduces risks of armed socio-political destabilization[2] and directly and positively affects economic growth (see, e.g., Mankiw et al. 1992; Lucas 2002; Bonnal and Yaya 2015; Mamoon and Murshed 2009). At the same time, rapid population growth coupled with insufficient economic growth causes an increase in the risks of armed destabilization. High population itself strongly and positively influences the risks of destabilization (Urdal 2008; Besançon 2005; Wimmer and Cederman 2009; Hegre and Sambanis 2006; Raleigh 2015). Armed political destabilization is strongly and negatively associated with economic growth (see, e.g., Aisen and Veiga 2013; Fosu 1992; Gates et al. 2012; Alesina et al. 1996). There is also a strong negative relationship between education and armed destabilization, which is supported empirically (see, e.g., Justino 2006; Østby et al. 2019; Ustyuzhanin and Korotayev 2023; Ustyuzhanin et al. 2022, 2023a, 2023b).

These theoretical assumptions are modelled using mathematical equations that are calculated for a certain country in a certain year: (1) the probability of an armed destabilization (a modified version of Cincotta and Weber 2021 model) and (2) economic development, taking into account this probability (based on the model by Aisen and Veiga 2013). Such models can be presented in the following form:

For armed destabilization:

.png) (Eq. 1)

(Eq. 1)

.png) ,

,

where g(cit) – logit function of the dependent variable cit (1 = armed uprising/civil war, 0 = its absence) for observation i at time t;

Pit, Mit and Eit – explaining variables of i observation at time t (population, median age, and education, respectively);

bit – estimated coefficients for the explanatory variables;

mt – specific time effect;

e it – the random errors of each observation i at time t.

To calculate the probability from the estimated g(cit), it is necessary to transform it into exponential form. Then the equation of the estimated probability of event cit will be:

.png) (Eq. 2)

(Eq. 2)

.png)

To evaluate economic growth, it makes sense to model first the overall level of economic development:

.png) (Eq. 3)

(Eq. 3)

.png)

where yit – GDP per capita of observation i at time t;

bi – estimated coefficients for the explanatory variables;

yi,t – 1 – GDP per capita of observation i at time t – 1 (lagged);

.png) – population

delta,

– population

delta,

where Pit – population of observation i at time t, and Pi,t – 1 – population of observation i at time t – 1 (lagged);

Mit – median age of observation i at time t;

Eit – education of observation i at time t;

e it – random errors of each observation i at time t;

.png) – probability

function of armed destabilization of observation i at time t,

which has the following form:

– probability

function of armed destabilization of observation i at time t,

which has the following form:

.png) (Eq. 4)

(Eq. 4)

.png)

.png)

where P(cit) is estimated probability of armed destabilization for observation i at time t.

Then economic growth can be modeled by following equitation:

.png) (Eq. 5)

(Eq. 5)

.png)

Based on this, the following scenarios are modeled:

1. The inertial scenario is based on the assumption that the trends of recent years will continue at the same pace in the respective countries (and in Sub-Saharan Africa [SSA] as a whole).

2. Pessimistic scenario of delayed modernization in SSA cannot be ruled out as there have already been precedents when, after a period of fairly rapid modernization (declining fertility rate, rapid expansion of formal education), many countries of the region experienced a noticeable slowdown. Thus, the attempts to save on education within the framework of structural adjustment programs in the 1990s caused delay in its spread that, in turn, led to remarkable slowdowns or, not infrequently, complete stalls of fertility decline (Schoumaker 2019; Zinkina and Korotayev 2017; Kebede et al. 2019).

3. Scenario of full achievement of the sustainable development goals (SDGs). When analyzing the impact of achieving the SDGs on fertility decline in Sub-Saharan countries, we rely on the calculations of the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) (Vollset et al. 2020).

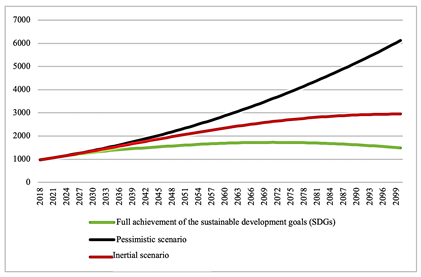

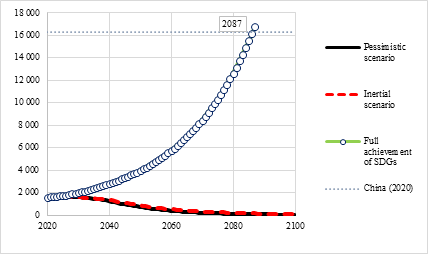

In terms of demographic characteristics, our inertial scenario corresponds to the reference scenario, and the pessimistic scenario corresponds to the scenario of slow achievement of the SDGs by the Institute for Health Metrics and Assessment (Ibid.). These scenarios produce the following projections of population dynamics in Sub-Saharan Africa (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Population growth scenarios (in millions) in Sub-Saharan Africa in the 21st century

Note that the pessimistic scenario (the upper black line in Fig. 6) is rather speculative. This scenario (as will be shown below) is fraught with the highest risks of socio-demographic and political-economic collapses in the not-too-distant future. Inertial scenario (the intermediate line), though less threatening, also bears rather serious risks of collapses, although in the noticeably more distant future. The only scenario that can secure stable development of the SSA countries withstanding the risks of socio-demographic and political-economic collapses is the scenario of a fairly rapid and full achievement of the SDGs.[3]

1.2. Forecast Scenarios for Countries

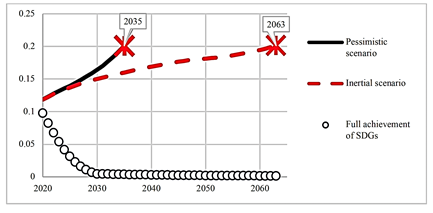

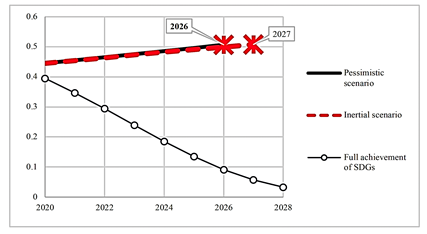

Let us now consider the results of modeling the demographic, economic and political future of some of the most important countries in Tropical Africa. We will start with presenting our results for Angola. To begin with, one should consider scenarios for the dynamics of the risks of armed destabilization/civil wars (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Angola

As will become clear from

comparison with other analyzed countries of Tropical Africa, Angola is

characterized by rather low risks of the outbreak

of large-scale civil wars. Even if the inertial scenario is followed,

noticeable risks of catastrophic civil wars in the country will appear only in

the second half of this century. Only a significant delay in moving towards the

achievement of the SDGs (primarily in the spread of modern education) can lead

to the emergence of such risks in the next

decade (a pessimistic scenario). At the same time, Angola will be able

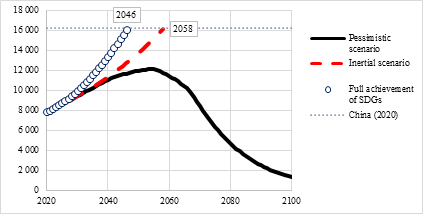

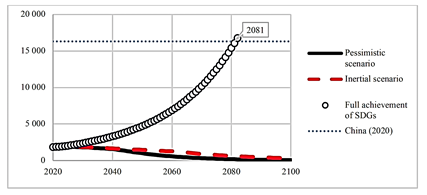

to reach the level of modern China in per capita GDP by 2058 even if it follows

the inertial scenario (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Scenarios for GDP per capita dynamics in Angola. Here and throughout GDP per capita is estimated in constant 2011 international dollars at purchasing power parities

However, if Angola follows the scenario of achieving the SDGs, it will be able to reach the level of modern China even before 2050. It should be noted that we refrain from predicting the further economic development of both Angola and other countries of Tropical Africa after reaching the level of modern China, since there is reason to expect that, after this, the development of the countries of Tropical Africa will most likely slow down due to the effect of the middle-income trap (on this trap, see, e.g., Glawe and Wagner 2016; Kharas and Kohli 2011; Matsuyama 2008; Azariadis and Stachurski 2005). Thus, for modeling the further development of the countries of Tropical Africa, the above mathematical model is no longer sufficient.

It should be noted that if the process of achieving the SDGs is completely disrupted, even if destructive civil wars do not start in Angola, we should expect a slowdown in economic development up to the negative economic growth rates, followed by the impoverishment of the population of Angola. However, even if this scenario is followed, per capita GDP in Angola will drop to only US$ 1,350 by 2100, which is still noticeably higher than this indicator, for example, in modern Niger (US$ 985). This shows that Angola has a sufficient margin of safety, a good economic base and relatively low risks of armed destabilization and impoverishment of the population.

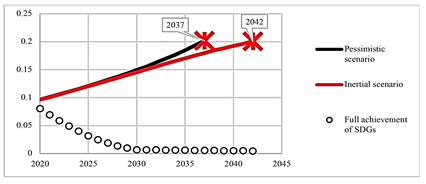

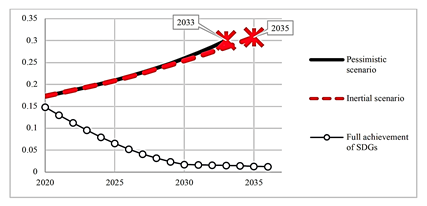

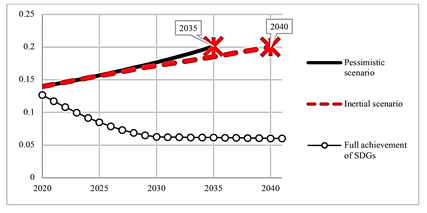

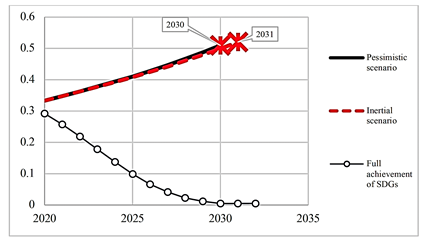

Tanzania is characterized by a noticeably higher level of risks, although it looks quite safe against the general background of the countries of Tropical Africa (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Tanzania

With the development according to the inertial scenario, serious risks of full-scale civil wars in this country will appear only in 2040. And with a significant delay in achieving the SDGs, ending or reducing the coverage of the population with formal education, Tanzania may face the risks of full-scale armed destabilization as early as 2030.

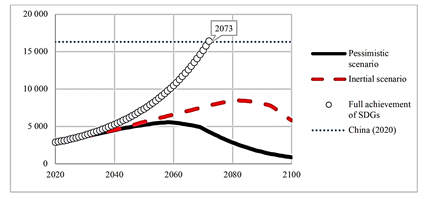

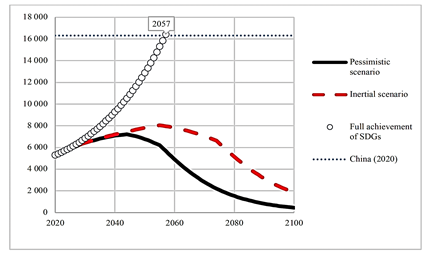

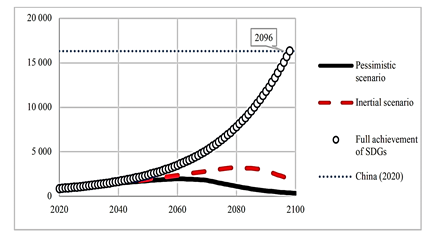

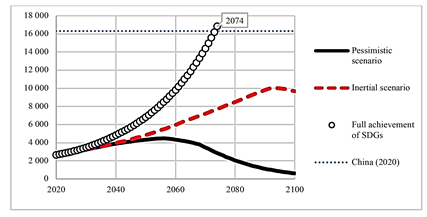

Under the SDG Fast Scenario, GDP per capita in Tanzania will reach the level of modern China in 2070 (see Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. GDP per capita scenarios in Tanzania

In the inertial scenario, Tanzania will not be able to exceed the US$ 9,000 level, and at the same time, at the end of the century, a systematic decline in the average levels of income of the country's population may begin. Under the scenario of significant underachievement of the SDGs, by the end of the century, even if Tanzania manages to avoid a large-scale political and demographic collapse, there will be a catastrophic impoverishment of the country's population with a drop in per capita GDP below US$ 1,000, which is less than the initial values in 2020.

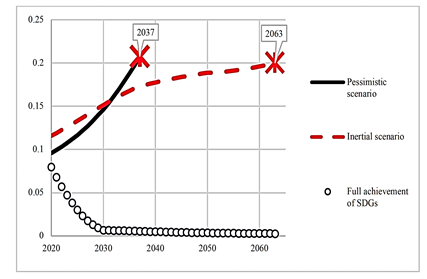

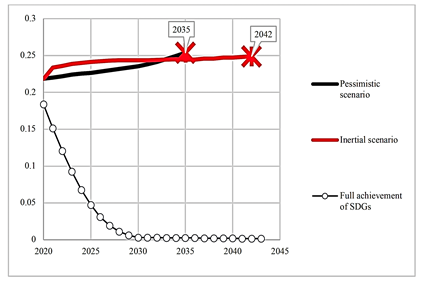

Quite similar scenarios can be traced for Uganda, wh ere the risks of a full-scale civil war with an inertia scenario are expected in the second half of this century, and, with a significant lag in achieving the SDGs, in the 2030s (see Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Uganda

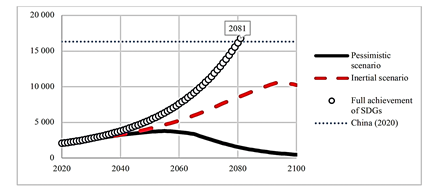

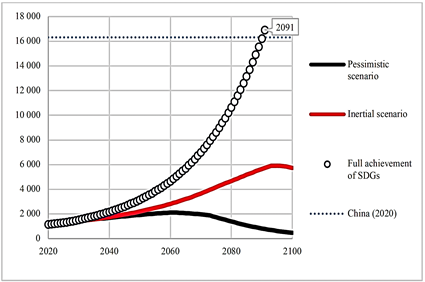

Uganda is expected to reach the level of the PRC in terms of per capita GDP under the scenario of rapid achievement of the SDGs in the second half of this century. It performs slightly better under the inertial scenario than Tanzania, but under a particularly significant SDG delay scenario, it is projected to be even more impoverished, with GDP per capita falling below US$ 500 (see Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. GDP per capita scenarios in Uganda

Ethiopia is characterized by extremely high risks of armed destabilization, full-scale civil wars and political and demographic collapses in the very coming years. At the same time, such risks are extremely high even in the case of development under the inertial scenario. To prevent them, a noticeable acceleration in the achievement of the SDGs is necessary (see Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Ethiopia

Accordingly, even the development according to the inertial scenario

assumes a significant impoverishment of the Ethiopian population in the coming

decades. However, an accelerated path to achieving the SDGs could allow

Ethiopia to reach the level of modern China in the second half of this century

(see Fig. 14).

Fig. 14. GDP per capita scenarios in Ethiopia

Somewhat lower, but still very high, are the risks of political-demographic collapses in Nigeria as well (see Fig. 15).

Fig. 15. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Nigeria

However, Nigeria's economic prospect looks somewhat less ominous. Per capita GDP growth in Nigeria may continue until the mid-century (albeit at a rather slow pace) even under the inertial scenario. In the case of the optimistic scenario, Nigeria could approach the level of modern China by the mid-century (see Fig. 16).

Fig. 16. GDP per capita scenarios in Nigeria

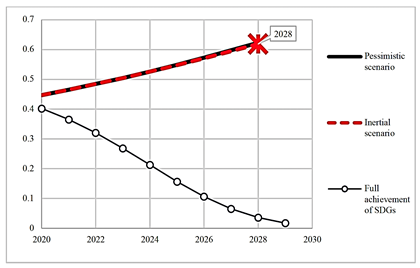

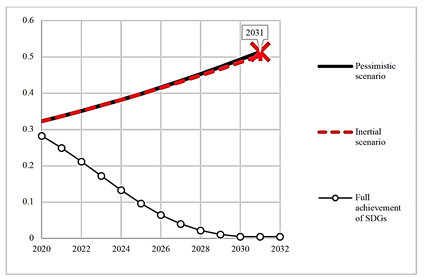

The risks of new full-scale civil wars are also extremely high in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (see Fig. 17).

Fig. 17. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in the DRC

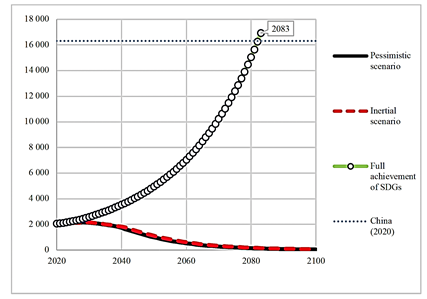

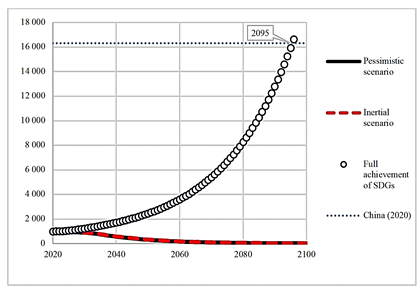

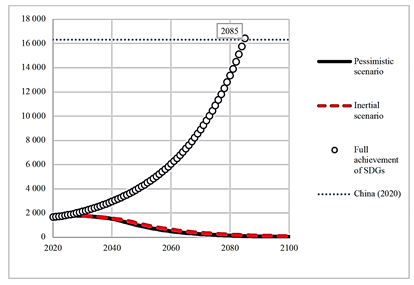

At the same time, the prospects for the economic development of the DRC seem noticeably worse than those of Nigeria: even with the development under the optimistic scenario, the DRC will be able to catch up with China in terms of its GDP per capita only by the very end of this century (see Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. GDP per capita scenarios in DR Congo

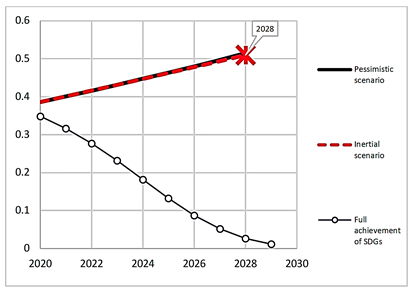

A very similar pattern is observed for Mozambique (see Figs 19 and 20) and Senegal (see Figs 21 and 22).

Fig. 19. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Mozambique

Fig. 20. GDP per capita scenarios in Mozambique

.png)

Fig. 21. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Senegal

Fig. 22. GDP per capita scenarios in Senegal

Finally, we are dealing with the highest (even by the standards of Tropical Africa) risks of political and demographic collapses in the Sahelian countries (Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, see Figs 23–44). All these countries are characterized by: (1) a very slight difference between the inertial scenario and the pessimistic scenario; (2) extremely high risks of full-scale civil wars in the very coming years; and (3) reaching the level of middle-income countries only by the end of this century, even under the most optimistic scenario.

Fig. 23. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Chad

Fig. 24. GDP per capita scenarios in Chad

Fig. 25. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Niger

Fig. 26. GDP per capita scenarios in Niger

Fig. 27. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Mali

Fig. 28. GDP per capita scenarios in Mali

Fig. 29. Scenarios of risk dynamics of armed destabilization/civil wars in Burkina Faso

Fig. 30. GDP per capita scenarios for Burkina Faso

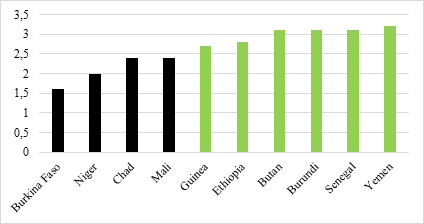

This is largely due to the fact that all these four countries occupy the lowest lines in the global ranking of countries in terms of population coverage with modern education (see Fig. 31).

Fig.

31. 10

countries in the world with the lowest mean years of schooling in 2018. Solid

black bars indicate the countries

of the G5 Sahel

Source: Korotayev and Ustyuzhanin 2021; UNDP database.

Meanwhile, as mentioned above, a very important factor in whether or not revolutionary actions in a country will take an armed form is the coverage of the population with formal education. In other words, armed revolutionary insurgencies / civil wars are most likely in the countries with a high proportion of illiterate or semi-literate population (Grinin and Korotayev 2009, 2014; Korotayev, Bilyuga, and Shishkina 2017a; Korotayev, Sawyer et al. 2020; Ustyu-zhanin et al. 2022; Collier 2004; Barakat and Urdal 2009; Machado et al. 2011; Brancati 2014; Butcher and Svensson 2016; Kostelka and Rovny 2019; Korotayev, Sawyer, and Romanov 2021; Sawyer and Korotayev 2022). The Sahelian countries belong to this category.

Of special concern is that the militant formations of Islamist radicals quite intentionally choose schools, teachers, and pupils as one of their main targets, in a deliberate attempt to reduce the coverage of the population with modern education. Thus, speaking about the events of 2020 in Burkina Faso, Rida Lammouri notes that Islamist militant groups

continued to sel ect schools as important targets for their attacks ... In its May 2020 report, Human Rights Watch (HRW) counted 126 attacks and armed threats against teachers, students, and schools by jihadist groups in 2020, in addition to 222 education workers who were victims of the attacks. Consequently, the Burkinabe government has closed around 2,500 schools, depriving about 350,000 students of education (Lyammouri 2020: 2–3).

And one of the most important radical Islamist groups in the Sahel, Boko Haram[4], has even used the slogan of combating the spread of modern education as its self-name (see, e.g., Walker 2012).

Thus, a dangerous feedback loop is being formed in the Sahel, leading to a vicious circle and a development trap, when the low coverage of the population with modern education stimulates the growth of armed revolutionary Islamist activity, and the growth of the latter, in turn, leads to a decrease in the coverage of the population with education, which can lead not only to further growth of armed activity of the Islamists, but also to a delay in the decline in the birth rate (or even to some fertility increase[5]), to an increase in the population growth rate, to a slowdown in economic growth, to a fall in per capita GDP, to the preservation or even growth of ‘youth bulges’, which will lead to an even more pronounced increase in the armed activities of radical Islamists. The countries of the Sahel need to break out of this trap as soon as possible, which, apparently, is no longer possible without the most serious support on the part of the world community.

2.

Brief Socio-Political Forecasts of the Futures

of Africa in a World-Systems Perspective

Thus, on the one hand, the African countries are ahead of the path of active and dynamic development in the demographic, economic, political, cultural and other spheres. But on the other hand, this development path seems to be very thorny, associated with a high risk of destabilization events, possible kickbacks and casualties.

As we see, on the one hand, Africa is a big problem for the modern World System in terms of poorly controlled population growth, which can lead to serious environmental, climatic, social, food and other problems that in one way or another will concern the entire World System. Therefore, the major powers are interested in making Africa's demographic development more manageable. But on the other hand, in the context of globally declining birth rates, it is African labor resources that can partially help solve the problem of labor shortages. Thus, developed countries need to develop a common program of influence on African countries in a direction more acceptable to humanity so that this program does not infringe on the interests of African states. Meanwhile, not enough attention has been paid to Africa so far. In addition, the world community faces the important challenge of trying to use the African resource as efficiently as possible to solve global problems, with the maximum benefit for the Africans themselves.

Rapid demographic growth and an increase in the proportion of young people, taking into account rapid urbanization, as is clear, will inevitably exacerbate the already acute problem of unemployment in African countries. However, in the world-system aspect, this can contribute to the development of both regions with an elderly population and Africa itself. With the rapid development of remote work (see Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b), more Africans will be connected with economically developed countries. In this regard, developed countries have a very important task to provide more assistance than is being done today in the development of the education system and the possible recruitment of specialists for remote work. This is a project for decades. And this is one of the ways to reduce unemployment in Africa, raise living standards in these countries, and bring European and African cultures closer together. There are also possible ways to bring European pension systems closer to the governments of African countries (for more details see Grinin and Korotayev 2010, 2016).

Taking into account global aging, which in the coming decades will greatly affect the situation in Europe, East Asia and other regions (see Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b, 2024), Africa's young societies – with all their future problems and instability – will positively influence the overall picture of the world's population in a number of aspects.

Rapid population growth in Africa against the background of declining fertility is creating and will continue to create a huge demographic dividend in many African countries (see, e.g., Bloom et al. 2013; Groth and May 2017; Jimenez and Pate 2017; Hasan et al. 2019; Korotayev, Shulgin et al. 2022). At present, of course, the poorly educated Tropical African working age population (especially females) is of little value to the world economy. However, as the level and quality of education increases, these cohorts can become a very powerful resource for the deficient working-age population of aging developed countries[6] as well as a source of youth for the education systems of these countries. Already today, a large number of African students study in European, American and Asian universities, a large number of specialists from Africa work in one way or another for these economies.

Although aging in African countries will begin to be felt substantially only in the second half of the 21st century, it is nevertheless, necessary to forecast that African countries are likely to meet this process completely unprepared if they do not begin to prepare for it in advance (which is doubtful, given the more acute and numerous problems they face). Meanwhile, although we have noted that almost all societies are severely underprepared for the consequences of global aging (see Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023b, 2024), African countries are prepared for this to a much lesser extent than, for example, European ones, since in African countries the pension and other social security systems are largely underdeveloped. One can say that they are only being formed. Perhaps, when the problems of aging become more pronounced, there will be already formed models of relations in society that contribute to the institutionalization of aging (for more details see Grinin, Grinin, and Malkov 2023; Grinin and Grinin 2023; Grinin et al. 2024).

We would like to conclude this article with a thesis formulation of some conclusions, from which it follows that destabilization processes will continue to take place in African countries in the future (although, of course, the scenario and the course of specific events will greatly depend on a number of circumstances) for many reasons. At the same time, implementing the right policies in the field of demography, education (especially for women), as well as in the ethno-national and economic spheres, as has been emphasized above, can significantly reduce the risks of such destabilizing events and their severity. It is worth noting here that the larger the population in the country, especially the young, the more acute conflicts and problems can be, so reducing the birth rate is the right way to reduce the risks and severity of destabilization problems.

Our general idea, which explains the inevitability under any circumstances of the emergence of destabilization processes both in the near and in the distant future of African countries, is the existence of a close correlation between immaturity / backwardness / underdevelopment and future instability events. And this correlation is as follows. As society matures, ideology, social, national and po-litical forces and conditions for certain processes appear in it, which can simultaneously influence destabilization. We mean the following factors: the desire for a nation state, for democracy and social justice, the desire to get their share of benefits and power from certain elites, the struggle for resources and privileges, the strengthening of contradictions between the regions of the country, and many others.[7] All this can lead to internal confrontation and, as a result, to possible destabilization. Modernization continues in the Sahel and many other regions in Africa. As a result, an increasingly complex conglomeration of the modern and the archaic in all spheres of production and life is being formed in these societies. The archaic features will, of course, disappear, but only after some time. And with rapid modernization, a tough conflict arises between the advanced and the archaic, which in itself is a source of instability. Let us now list the reasons for this in more detail.

First, the overall impact of the World System reconfiguration processes will be felt (see Grinin and Korotayev 2012, 2015, 2023; Grinin 2022a). And this impact, other things being equal, is the more noticeable and stronger, the more unstable the socio-political and ethno-confessional situation in a particular region is. Africa is an extremely unstable and conflict zone, so various global processes will inevitably be reflected in it in the form of certain destabilizing events.

Second, Africa, including the Sahel zone and North Africa, as well as its other zones and countries (e.g., the Democratic Republic of the Congo), is becoming a territory of increasing geopolitical rivalry between major powers.

Third, under external pressure, a synergistic effect can arise with an internal weakness and instability of such states and societies.

Fourth, the weakness of society in such cases is very often associated with:

a) the point that in the recent past it was an artificial political formation whose boundaries were drawn for political reasons by external political actors;

b) the fact that there are no strong traditions of statehood; society is not ethnically monolithic, but divided, while conflicts between different ethnic groups, cultures, confessions, territories, tribes or clans are very significant, and also easily flare up.

Fifth, most countries of the Afrasian instability macrozone[8] correspond to one or more of the listed parameters to a greater or lesser extent, not to mention the fact that in the Sahel and other regions of Africa there are so-called failed states (e.g., Korotayev, Medvedev et al. 2022) that unable to resist criminal and terrorist groups to protect their own population (see above). Accordingly, it is quite possible to expect various problems in such countries.

Thus, it can be assumed that for a number of global, regional, cultural, religious and country reasons, many African societies will experience increased risks of destabilization for quite a long time. At the same time, a set of destabilization phenomena will often be present in societies, that is, several components of destabilization (revolutions, civil wars, confessional confrontations, interventions, terrorism, etc.) will simultaneously interact, hybridizing, which, unfortunately, can open unstable eras (like the one that we could observe in the recent decades in the Democratic Republic of the Congo). And the period of overcoming these shortcomings and maturation of societies will also be a period of extremely high risk of destabilization processes.

However, we believe that African societies have a bright future ahead and, in general, Africa will increasingly contribute to the world-system development.

References

Aisen A., and Veiga F. J. 2013. How does Political Instability Affect Economic Growth? European Journal of Political Economy 29: 151–167.

Alesina A., Özler S., Roubini N., and Swagel P. 1996. Political Instability and Economic Growth. Journal of Economic Growth 1(2): 189–211.

Azariadis C., and Stachurski J. 2005. Poverty Traps. Handbook of Economic Growth / Ed. by S. N. Durlauf, and P. Aghion, pp. 295–384. Elsevier.

Barakat B., and Urdal H. 2009. Breaking the Waves? Does Education Mediate the Relationship Between Youth Bulges and Political Violence? World Bank.

Besançon M. L. 2005. Relative Resources: Inequality in Ethnic Wars, Revolutions, and Genocides. Journal of Peace Research 42(4): 393–415

Bloom D. E., and Williamson J. G. 1998. Demographic Transitions and Economic Miracles in Emerging Asia. World Bank Economic Review 12(3): 419–455.

Bloom D. E., Canning D., and Malaney P. 2000. Demographic Change and Economic Growth in Asia. Population and Development Review 26(suppl): 257–290.

Bloom D. E., Canning D., and Sevilla J. 2003. The Demographic Dividend: A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change. RAND.

Bloom D. E., Humair S., Rosenberg L., Sevilla J. P., and Trussell J. 2013. A Demographic Dividend for Sub-Saharan Africa: Source, Magnitude, and Realization. IZA.

Bonnal M., and Yaya M. E. 2015. Political Institutions, Trade Openness, and Economic Growth: New Evidence. Emerging Markets: Finance and Trade 51: 1276–1291. Doi:10.1080/1540496x.2015.1011514

Brancati D. 2014. Pocketbook Protests: Explaining the Emergence of Pro-Democracy Protests Worldwide. Comparative Political Studies 47(11): 1503–1530.

Butcher C., and Svensson I. 2016. Manufacturing Dissent: Modernization and the Onset of Major Nonviolent Resistance Campaigns. Journal of Conflict Resolution 60(2): 311–339.

Choucri N. 1974. Population Dynamics and International Violence: Propositions, Insights, and Evidence. Lexington Books.

Cincotta R., and Weber H. 2021. Youthful Age Structures and the Risks of Revolutionary and Separatist Conflicts. Global Political Demography: Comparative Analyses of the Politics of Population Change in All World Regions / Ed. by A. Goerres, and P. Vanhuysse, pp. 57–92. Palgrave Macmillan.

Collier P. 2004. Greed and Grievance in Civil War. Oxford Economic Papers 56(4): 563–595.

Farzanegan M. R., and Witthuhn S. 2017. Corruption and Political Stability: Does the Youth Bulge Matter? European Journal of Political Economy 49: 47–70. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.12.007

Fosu A. K. 1992. Political Instability and Economic Growth: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Development and Cultural Change 40: 829–841. https:// doi.org/10.1086/451979

Gates S., Hegre H., Nygård H. M., and Strand H. 2012. Development Consequences of Armed Conflict. World Development 40: 1713–1722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.04.031

Glawe L., and Wagner H. 2016. The Middle-Income Trap: Definitions, Theories and Countries Concerned. A Literature Survey. Comparative Economic Studies 58(4): 507–538.

Goldstone J. A. 1991. Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World. University of California Press.

Goldstone J. A. 2001. Demography, Environment, and Security: An Overview. Demography and National Security / Ed. by M. Weiner, and S. S. Russell, pp. 38–61. Berghahn Books.

Goldstone J. A. 2002. Population and Security: How Demographic Change Can Lead to Violent Conflict. Journal of International Affairs 56(1): 3–21.

Goldstone J. A., Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2022. Conclusion. How Many Revolutions Will We See in the 21st Century? Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st Century: The New Waves of Revolutions and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change / Ed. by J. A. Goldstone, L. Grinin, and A. Korotayev, pp. 1037–1061. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_41

Goldstone J. A., Kaufmann E. P., and Toft M. D. 2012. Political Demography: How Population Changes Are Reshaping International Security and National Politics. Oxford University Press.

Grinin L. 2012. State and Socio-Political Crises in the Process of Modernization. Cliodynamics 3(1): 124–157.

Grinin L. 2013. State and Socio-Political Crises in the Process of Modernization. Social Evolution & History 12(2): 35–76.

Grinin L. 2022a. On Revolutionary Situations, Stages of Revolution, and Some Other Aspects of the Theory of Revolution. Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st Century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change / Ed. by J. A. Goldstone, L. Grinin, and A. Korotayev, pp. 69–104. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_3

Grinin L. 2022b. Revolutions and Modernization Traps. Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st Century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change / Ed. by J. A. Goldstone, L. Grinin, and A. Korotayev, pp. 219–238. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_8

Grinin L., and Grinin A. 2022. Conclusion. New Wave of Middle Eastern Revolutionary Events in the World System Context. New Wave of Revolutions in the MENA Region. A Comparative Perspective / Ed. by L. Issaev, and A. Korotayev, pp. 257–274. Springer.

Grinin L., and Grinin A. 2023. Analyzing Social Self-Organization and Historical Dynamics. Future Cybernetic W-Society: Socio-Political Aspects. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 491–519. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_21

Grinin L., Grinin A., and Korotayev A. 2023a. Future Political Change. Toward a More Efficient World Order. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 191–206. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_11

Grinin L., Grinin A., and Korotayev A. 2023b. Global Aging – an Integral Problem of the Future. How to Turn a Problem into a Development Driver? Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 117–135. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_7

Grinin L., Grinin A., and Korotayev A. 2024. Cybernetic Revolution and Global Aging: Humankind on the Way to Cybernetic Society, or the Next Hundred Years. Cham: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-56764-3

Grinin L., Grinin A., and Malkov S. 2023. Socio-Political Transformations. A Difficult Path to Cybernetic Society. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 169–189. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_10

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2009. Urbanization and Political Instability: To the Development of Mathematical Models of Political Processes. Politicheskiye Issledovaniya 4: 34–52. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В. Урбанизация и политическая нестабильность: к разработке математических моделей политических процессов. Политические исследования 4: 34–52).

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2010. Will the Global Crisis Lead to Global Transformations? The Coming Epoch of New Coalitions. Journal of Globalization Studies 1(2): 166–183.

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2012. Does ‘Arab Spring’ Mean the Beginning of World System Reconfiguration? World Futures 68(7): 471–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2012.697836

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2014. Revolution vs Democracy (Revolution and Counterrevolution in Egypt). Polis-Politicheskiye issledovaniya 3: 139–158. In Russian (Гринин Л., Коротаев А. Революция против демократии (Революция и контрреволюция в Египте). Полис 3: 139–158. https://doi.org/10.17976/jpps/2014.03.09

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2015. Great Divergence and Great Convergence. A Global Perspective. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17780-9

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2016. Global Population Ageing, the Sixth Kondratieff Wave, and the Global Financial System. Journal of Globalization Studies 7(2): 11–31.

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2023. The Future of Revolutions in the 21st Century and the World System Reconfiguration. World Futures 79(1): 69–90.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2022.2050342

Groth H., and May J. F. (Eds.) 2017. Africa's Population: In Search of a Demographic Dividend. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46889-1

Hasan R., Loevinsohn B., Moucheraud C., Ahmed S. A. et al. 2019. Nigeria's Demographic Dividend? Policy Note in Support of Nigeria's ERGP 2017–2020. World Bank.

Hegre H., and Sambanis N. 2006. Sensitivity Analysis of Empirical Results on Civil War Onset. Journal of Conflict Resolution 50(4): 508–535.

Jimenez E., and Pate M. A. 2017. Reaping a Demographic Dividend in Africa's Largest Country: Nigeria. Africa's Population: In Search of a Demographic Dividend / Ed. by H. Groth, and J. F. May, pp. 33–52. Springer.

Justino P. 2006. On the Links Between Violent Conflict and Chronic Poverty: How Much Do We Really Know? Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.

Kebede E., Goujon A., and Lutz W. 2019. Stalls in Africa's Fertility Decline Partly Result from Disruptions in Female Education. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(8): 2891–2896. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1717288116

Kharas H., and Kohli H. 2011. What is the Middle-Income Trap, Why do Countries Fall into It, and How Can It be Avoided? Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies 3(3): 281–289.

Korotayev A., Bilyuga S., and Shishkina A. 2016. GDP Per Capita, Protest Intensity and Regime Type: A Quantitative Analysis. Sravnitelnaya Politika 7(4): 72–94. https://doi.org/10.18611/2221-3279-2016-7-4(25)-72-94

Korotayev A., Bilyuga S., and Shishkina A. 2017a. Correlation between GDP per Capita and Protest Intensity: A Quantitative Analysis. Polis – Politicheskiye Issledovaniya 2: 155–169. In Russian (Коротаев А., Билюга С., Шишкина А. Корреляция между ВВП на душу населения и интенсивностью протестов: количественный анализ. Полис 2: 155–169. https://doi.org/10.17976/jpps/2017.02.1

Korotayev A., Bilyuga S., and Shishkina A. 2017b. GDP per Capita, Intensity of Anti-Government Demonstrations and Level of Education. Cross-National Analysis. Politiya 84(1): 127–143. In Russian (Коротаев А., Билюга С., Шишкина А. ВВП на душу населения, интенсивность антиправительственных демонстраций и уровень образования. Кросс-национальный анализ. Полития 84(1): 127–143). https://doi.org/10.30570/2078-5089-2017-84-1-127-143

Korotayev A., Bilyuga S., and Shishkina A. 2018. GDP per Capita and Protest Activity: A Quantitative Reanalysis. Cross-Cultural Research 52(4): 406–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397117732328

Korotayev A., Grinin L., Medvedev I., and Slav M. 2022. Political Regime Types and Revolutionary Destabilization Risks in the Twenty-First Century. Sotsiologicheskoye obozreniye 21(4): 9–65. In Russian (Коротаев А., Гринин Л., Медведев И., Слав М. Типы политических режимов и риски революционной дестабилизации в XXI ве-ке. Социологическое обозрение 21(4): 9–65). https://doi.org/10.17323/1728-192x-2022-2-9-65

Korotayev A., Issaev L., Shishkina A., Rudenko M., and Ivanov E. 2016. Afrasian Instability Zone and Its Historical Background. Social Evolution and History 15(2): 120–140.

Korotayev A., Issaev L., and Zinkina J. 2015. Center-Periphery Dissonance as a Possible Factor of the Revolutionary Wave of 2013–2014: A Cross-National Analysis. Cross-Cultural Research 49(5): 461–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397115595374.

Korotayev A., Malkov S., and Grinin L. 2014. A Trap at the Escape from the Trap? Some Demographic Structural Factors of Political Instability in Modernizing Social Systems. History & Mathematics: Trends and Cycles / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, and A. V. Korotayev, pp. 201–267. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Korotayev A., Medvedev I., and Zinkina J. 2022. Global Systems for Sociopolitical Instability Forecasting and Their Efficiency. A Comparative Analysis. Comparative Sociology 21(1): 64–104. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-bja10050

Korotayev A., Meshcherina K., Slinko E., and Shishkina A. 2019. Value Orientations of the Afrasian Zone of Instability: Gender Dimensions. Vostok (Oriens) 1: 122–154. In Russian (Коротаев А., Мещерина К., Слинько Е., Шишкина А. Ценностные ориентации в афразийской зоне нестабильности: Гендерные измерения. Восток (Oriens) 1: 122–154. https://doi.org/10.31857/S086919080003963-6

Korotayev A., Romanov D., Zinkina J., and Slav M. 2023. Urban Youth and Terrorism: A Quantitative Analysis (Are Youth Bulges Relevant Anymore?). Political Studies Review 21(3): 550–574. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299221075908

Korotayev A., Sawyer P., Gladyshev M., Romanov D., and Shishkina A. 2021. Some Sociodemographic Factors of the Intensity of Anti-Government Demonstrations: Youth Bulges, Urbanization, and Protests. Russian Sociological Review 20(3): 98–128. https://doi.org/10.17323/1728-192x-2021-3-98-128

Korotayev A., Sawyer P., Grinin L., Romanov D., and Shishkina A. 2020. Socio-Economic Development and Anti-Government Protests in the Light of a New Quantitative Analysis of Global Databases. Sotsiologicheskiy Zhurnal 26(4): 61–78. In Russian (Коротаев А., Сойер П., Гринин Л., Романов Д., Шишкина А. Социально-экономическое развитие и антиправительственные протесты в свете нового количественного анализа глобальных баз данных. Социологический журнал 26(4): 61–78). https://doi.org/10.19181/socjour.2020.26.4.7642

Korotayev A., Sawyer P., and Romanov D. 2021. Socio-Economic Development and Protests. A Quantitative Reanalysis. Comparative Sociology 20(2): 195–222. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-bja10030

Korotayev A., and Shishkina A. 2020. Relative Deprivation as a Factor of Sociopolitical Destabilization: Toward a Quantitative Comparative Analysis of the Arab Spring Events. Cross-Cultural Research 54(2–3): 296–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397119882364

Korotayev A., Shulgin S., Zinkina J., and Slav M. 2022. Estimates of the Possible Economic Effect of the Demographic Dividend for Sub-Saharan Africa for the Period up to 2036. Vostok (Oriens) 2: 108–123. In Russian (Коротаев А., Шульгин С., Зинькина Ю., Слав М. К оценке возможного экономического эффекта демографического дивиденда для стран Африки южнее Сахары для периода до 2036 года. Восток (Oriens): 2: 108–123). https://doi.org/10.31857/S086919080019128-7

Korotayev A., Vaskin I., and Bilyuga S. 2017. Olson-Huntington Hypothesis on a Bell-Shaped Relationship Between the Level of Economic Development and Sociopolitical Destabilization: A Quantitative Analysis. Sotsiologicheskoye obozreniye 16(1): 9–49. https://doi.org/10.17323/1728-192X2017-1-9-49

Korotayev A., Vaskin I., Bilyuga S., and Ilyin I. 2018.

Economic Development and Sociopolitical Destabilization: A Re-Analysis. Cliodynamics

9(1): 59–118. https://

doi.org/10.21237/c7clio9137314

Korotayev A., Vaskin I., and

Tsirel S. 2021. Economic Growth, Education, and Terrorism: A Re-Analysis. Terrorism and Political Violence 33(3):

572–595. https://

doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1559835

Korotayev A., and Ustyuzhanin V. 2021. On Structural and Demographic Factors of Violent Islamist Revolutionary Uprisings in the G5 Sahel Countries. System Monitoring of Global and Regional Risks 12: 451–474. In Russian (Коротаев А., Устюжанин В. О структурно-демографических факторах насильственных исламистских революционных выступлений в странах группы G5 Сахель. Системный мониторинг глобальных и региональных рисков 12: 451–474).

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., Goldstone J., and Shulgin S. 2016. Explaining Current Fertility Dynamics in Tropical Africa from an Anthropological Perspective: A Cross-Cultural Investigation. Cross-Cultural Research 50(3): 251–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397116644158

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., Kobzeva S. et al. 2011. A Trap at the Escape from the Trap? Demographic-Structural Factors of Political Instability in Modern Africa and West Asia. Cliodynamics 2(2): 276–303. http://doi.org/10.21237/C7clio22217.

Kostelka F., and Rovny J. 2019. It's Not the Left: Ideology and Protest Participation in Old and New Democracies. Comparative Political Studies 52(11): 1677–1712. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019830717

Lucas R.E. 2002. Lectures on Economic Growth. Harvard University Press.

Lyammouri R. 2020. Burkina Faso Elections, Another Box to Check. Policy Center for the New South. URL: https://www.policycenter.ma/sites/default/files/PB_20-84_Rida%20Lyammouri_n.pdf.

Machado

F., Scartascini C., and Tommasi M. 2011. Political Institutions and Street Protests in Latin

America. Journal of Conflict Resolution 55(3):

340–365. https://

doi.org/10.1177/0022002711400864

Mamoon D., and Murshed S. M. 2009. Want Economic Growth with Good Quality Institutions? Spend on Education. Education Economics 17: 445–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645290801931782

Mankiw N. G., Romer D., and Weil D. N. 1992. A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107(2): 407–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118477

Matsuyama K. 2008. Poverty Traps. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics / Ed. by S. N. Durlauf, and L. Blume, pp. 5073–5077. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-58802-2_1317

May J. F., and Rotenberg S. 2020. A Call for Better Integrated Policies to Accelerate the Fertility Decline in Sub‐Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning 51(2): 193–204.

Mesquida C. G., and Wiener N. I. 1996. Human Collective Aggression: A Behavioral Ecology Perspective. Ethology and Sociobiology 17(4): 247–262.

Mesquida C. G., and Weiner

N. I. 1999. Male Age Composition and Severity of Conflicts. Politics and the Life Sciences 18:

113–117. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0730938

400021158

Moller H. 1968. Youth as a Force in the Modern World. Comparative Studies in Society and History 10(3): 237–260. https://doi.org/10.2307/177801

Nzimande N., and Mugwendere T. 2018. Stalls in Zimbabwe Fertility: Exploring Determinants of Recent Fertility Transition. Southern African Journal of Demography 18(1): 59–110.

Omoruyi E. M. M. 2021. Harnessing the Demographic Dividend in Africa through Lessons from East Asia's Experience. Journal of Comparative Asian Development 18(2): 1–38.

Østby G., Urdal H., and Dupuy K. 2019. Does Education Lead to Pacification? A Systematic Review of Statistical Studies on Education and Political Violence. Review of Educational Research 89(1): 46–92. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318800236

Raleigh C. 2015. Urban Violence Patterns Across African States. International Studies Review 17(1): 90–106.

Romanov D., Meshcherina K., and Korotayev A. 2021. The Share of Youth in the Total Population as a Factor of Intensity of Non-Violent Protests: A Quantitative Analysis. Polis. Political Studies 3: 166–181. https://doi.org/10.17976/jpps/2021.03.11

Sawyer P., and Korotayev A. 2022. Formal Education and Contentious Politics: The Case of Violent and Non-Violent Protest. Political Studies Review 20(3): 366–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929921998210

Sawyer P., Romanov D., Slav M., and Korotayev A. 2022. Urbanization, the Youth, and Protest: A Cross-National Analysis. Cross-Cultural Research 56(2–3): 125–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/10693971211059762

Schoumaker B. 2019. Stalls in Fertility Transitions in Sub‐Saharan Africa: Revisiting the Evidence. Studies in Family Planning 50(3): 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12098

Slav M., Smyslovskikh E., Novikov V., Kolesnikov I., and Korotayev A. 2021. Deprivation, Instability, and Propensity to Attack: How Urbanization Influences Terrorism. International Interactions 47(6): 1100–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2021.1924703

Slinko E., Bilyuga S., Zinkina J., and Korotayev A. 2017. Regime Type and Political Destabilization in Cross-National Perspective: A Re-Analysis. Cross-Cultural Research 51(1): 26–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397116676485

Staveteig S. 2005. The Young and the Restless: Population Age Structure and Civil War. Environmental Change and Security Program Report 11: 12–19.

UN Population Division 2022. United Nations Population Division Database. United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Division. URL: http://www.un.org/esa/population.

Urdal H. 2004. The Devil in the Demographics: The Effect of Youth Bulges on Domestic Armed Conflict, 1950–2000. World Bank.

Urdal H. 2006. A Clash of Generations? Youth Bulges and Political Violence. International Studies Quarterly 50(3): 607–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00416.x

Urdal H. 2008. Population, Resources, and Political Violence: A Subnational Study of India, 1956–2002. Journal of Conflict Resolution 52(4): 590–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002708316741

Ustyuzhanin V., Grinin L., Medvedev I., and Korotayev A. 2022. Education and Revolutions. Why do Some Revolutions Take Up Arms While Others do not? Politiya. Analysis. Chronicle. Forecast. 104(1): 50–71. In Russian (Устюжанин В., Гринин Л., Медведев И., Коротаев А. Образование и революции (почему революционные выступления принимают вооруженную или невооруженную форму?) Полития. Анализ. Хроника. Прогноз. 104(1): 50–71. https://doi.org/10.30570/2078-5089-2022-104-1-50-71

Ustyuzhanin V., and Korotayev A. 2023. Education and Revolutions. Why do Revolutionary Uprisings Take Violent or Nonviolent Forms? Cross-Cultural Research 57(4): 352–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/10693971231162231

Ustyuzhanin V., Sawyer P. S., and Korotayev A. 2023a. Students and Protests: A Quantitative Cross-National Analysis. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 64(4): 375–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207152221136042

Ustyuzhanin V., Stepanishcheva Y., Gallyamova A., Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2023b. Education and Revolutionary Destabilization Risks: A Quantitative Analysis. Russian Sociological Review 22(1): 98–128. https://doi.org/10.17323/1728-192X-2023-1-98-128

Vaskin I., Tsirel S., and Korotayev A. 2018. Economic Growth, Education and Terrorism: Experience in Quantitative Analysis. Sotsiologicheskiy zhurnal 24(2): 28–65. https://doi.org/10.19181/socjour.2018.24.2.5844

Vollset S. E., Goren E., Yuan C.-W., Cao J., et al. 2020. Fertility, Mortality, Migration, and Population Scenarios for 195 Countries and Territories fr om 2017 to 2100: A Forecasting Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet 396: 1285–1306. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30677-2

Walker A. 2012. What is Boko Haram? US Institute of Peace.

Weber H. 2019. Age Structure and Political Violence: A Re-Assessment of the ‘Youth Bulge’ Hypothesis. International Interactions 45(1): 80–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2019.1522310

Wimmer A., and Cederman L.E., and Min B. 2009. Ethnic Politics and Armed Conflict: A Configurational Analysis of a New Global Data Set. American Sociological Review 74(2): 316–337.

Zinkina J., and Korotayev A. 2014a. Explosive Population Growth in Tropical Africa: Crucial Omission in Development Forecasts (Emerging Risks and Way Out). World Futures 70(4): 271–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2014.894868

Zinkina J., and Korotayev A. 2014b. Projecting Mozambique's Demographic Futures. Journal of Futures Studies 19(2): 21–40.

Zinkina J., and Korotayev A. 2017. Socio-Demographic Development of Tropical African Countries: Key Risk Factors, Modifiable Control Parameters, Recommendations. LENAND. In Russian (Зинкина Ю., Коротаев А. В. Социально-демографическое развитие стран Тропической Африки: Ключевые факторы риска, модифицируемые управляющие параметры, рекомендации. ЛЕНАНД).

* This research has been implemented with the support of the Russian Science Foundation (Project № 24-18-00650).

[1] See, e.g., Moller 1968; Choucri 1974; Mesquida and Wiener 1996, 1999; Goldstone 1991, 2001, 2002; Urdal 2004, 2006, 2008; Staveteig 2005; Korotayev et al. 2011, 2014; Goldstone, Kaufmann, and Toft 2012; Farzanegan and Witthuhn 2017; Weber 2019; Cincotta and Weber 2021; Romanov et al. 2021; Korotayev, Sawyer, Gladyshev et al. 2021; Korotayev, Romanov et al. 2023; Sawyer et al. 2022.

[2] The diffusion of formal education in low- and middle-income countries simultaneously leads to an increase in the risks of unarmed destabilization (e.g., Korotayev, Bilyuga, and Shishkina 2017b, 2018; Korotayev, Sawyer, Grinin et al. 2020; Korotayev, Sawyer, and Romanov 2021; Sawyer and Korotayev 2022; Ustyuzhanin and Korotayev 2023; Ustyuzhanin et al. 2022, 2023a, 2023b) while reducing the risks of armed revolutions/civil wars (Urdal 2008; Østby et al. 2019; Ustyu-zhanin and Korotayev 2023; Ustyuzhanin et al. 2022, 2023a, 2023b). However, these are armed insurgencies/civil wars that have a really strong negative impact on economic growth. Thus, education reduces namely those risks that negatively affect economic growth. Therefore, the impact of the spread of formal education through this channel on economic growth is rather positive, which is also confirmed in models of neoclassical economic growth.

[3] Taking into account the fact that under any demographic scenario these countries follow the path of modernization, and this period is always more prone to processes of destabilization and revolutions, as well as due to immature statehood, the growth of nationalism (often in the form of ethnic tribalism), the risks of socio-political destabilization in SSA countries remain very high (Korotayev et al. 2011; Goldstone et al. 2022; Grinin 2022b; Grinin and Grinin 2022).

[4] A terrorist organization banned in Russia.

[5] See, e.g., Zinkina, Korotayev 2014a, 2014b, 2017.

[6] See Grinin, Grinin, and Korotayev 2023a, 2023b.

[7] See, e.g., Korotayev et al. 2011, 2015; Grinin 2012, 2013, 2022a; Korotayev, Malkov, and Grinin 2014; Korotayev, Bilyuga, and Shishkina 2016, 2017a, 2017b, 2018; Korotayev, Vaskin, and Bilyuga 2017; Slinko et al. 2017; Korotayev, Vaskin, Bilyuga et al. 2018; Vaskin et al. 2018; Korotayev and Shishkina 2020; Korotayev, Vaskin, and Tsirel 2021; Slav et al. 2021; Korotayev, Grinin et al. 2022.

[8] On the Afrasian instability macrozone see, e.g., Korotayev, Issaev et al. 2016; Korotayev, Meshcherina et al. 2019.